Intel’s new CEO has promised to clean up the balance sheet, slim down the company, return to a culture of engineering, sharpen its customer focus, shore up its products, become a world class independent foundry and lead Intel for as long as it takes to achieve success – however that is defined. As our audience knows, unlike most other analysts, we have aggressively emphasized the icebergs ahead for Intel since 2013, culminating in our prediction that Intel would go bankrupt trying to execute on its most previous strategy. While we would have preferred a different approach to Intel’s foundry – i.e. a JV with TSM – Lip-Bu Tan at least has what we consider to be a viable go forward plan. The steady state outcome of this new direction, however is far from certain.

Our current thinking is, in addition to LBT’s cost cutting, cultural do-over and other structural changes, that Intel must execute on the following four strategies:

- Refocus products on its core PC / device heritage to win back that market before others fill the gaps it has opened;

- Innovate on the product side in AI PCs, edge and robotics by drafting off of NVIDIA’s AI successes – but filling what we see as holes in NVIDIA’s product capabilities;

- Intelligently partner with TSMC, Arm and RISC-V for Intel’s own designs; and

- Keep its foot in the foundry door as a precious resource for the US on-shore advanced manufacturing.

In this Breaking Analysis we update you on our latest thinking about where Intel is now headed. We’ll review some striking data on Intel’s ascendency, how its fall from grace eerily echoes that of IBM’s thirty-five years ago, the daunting task of competing in foundry, it’s product outlook going forward, how we would approach its future and a map of how the data center landscape has changed and what it will look like in the coming decades.

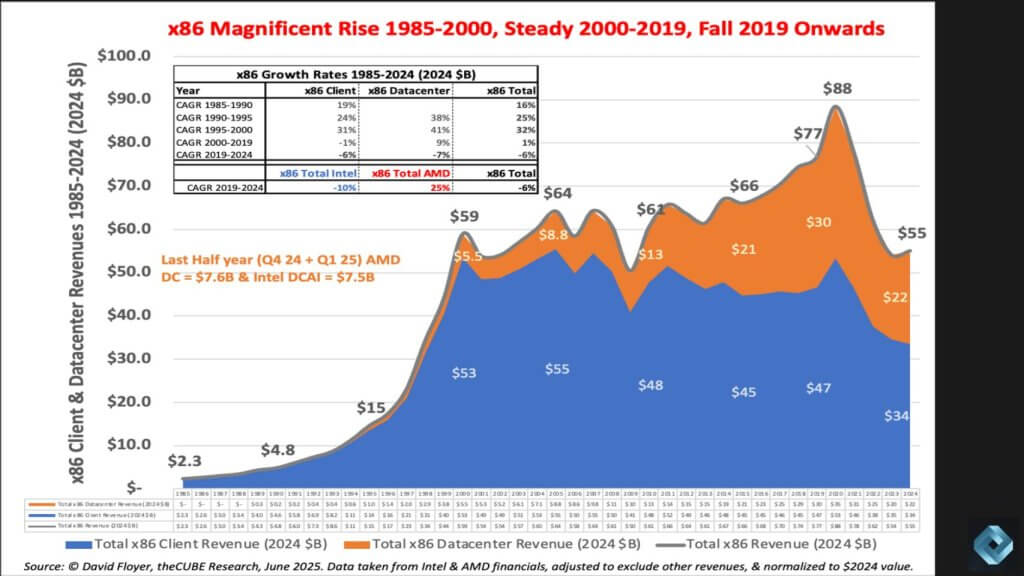

The Rise and Fall of x86: A Magnificent Run Faces Harsh Realities

Few technology narratives rival the dominance – and the subsequent reversal of fortune – of the x86 architecture. One of those narratives – i.e. IBM’s fall from dominance – has similar dimensions and is one we’ll draw upon today as a guidepost to the future. The story of Intel’s rise through the 1980s into the early 2000s is one of relentless execution, volume leverage, and ecosystem advantage. As shown below in Exhibit 1, x86 revenues grew from modest beginnings in the mid-80s to become the heart of both client and data center computing.

Our research indicates that this expansion was driven by several foundational advantages:

- Volume economics from the PC era enabled Intel to leverage fabrication and design scale.

- Superior price-performance compared to legacy minicomputers and RISC-based Unix systems.

- A powerful and sticky developer ecosystem that formed around x86 over decades.

- Consistent execution in client computing, followed by aggressive moves into the server market.

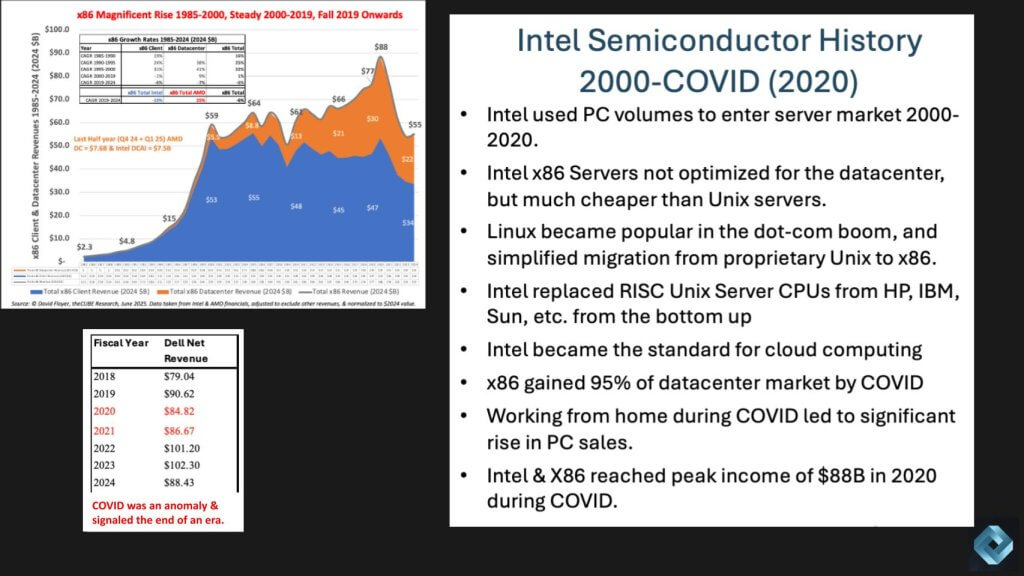

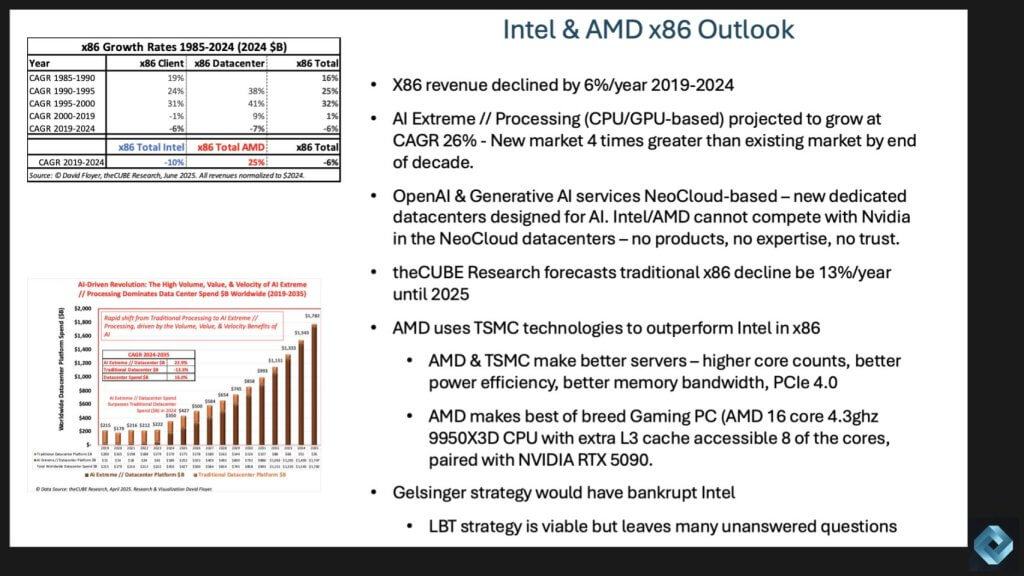

From 1995 to 2000, x86 revenues grew at an impressive compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 32% overall and 41% in the data center sector. Intel’s momentum carried through the 2000s, but as the chart makes clear, the story changed as time progressed. While COVID briefly reinvigorated x86 revenues due to a surge in demand for PCs, with the shift to parallel processing, it’s became clear to everyone finally that the architecture is facing a secular decline.

Specifically:

- Client revenue has steadily declined, from a peak of $55B in the early 2000s to an estimated $34B in 2024.

- Data center revenue, once a source of growth, has also stagnated, dropping to around $22B in 2024, despite AMD’s successes – It has gained meaningful share at the expense of Intel.

- The total x86 revenue CAGR from 2019–2024 is negative 6%, with Intel’s data center business down 10%, while AMD has grown 25% over the same period.

In our view, the COVID spike masked structural weaknesses in the x86 market. As alternative architectures – especially ARM-based designs — gained traction in cloud, mobile, and now even AI, the moat that once protected Intel has deteriorated. Nonetheless, it’s important to acknowledge the sheer scale and historical success of this architecture. As David Floyer aptly put it, this was a “magnificent journey” driven by Intel’s mastery of both PC and server economics.

We believe the x86 story is now well beyond its turning point. The architecture that once swept aside its predecessors is facing its own moment of reckoning – a pattern we’ll explore further as we dive into Intel’s current strategy and long-term bets.

Wintel’s Golden Age: Volume, Value, and Velocity

To understand Intel’s current situation, it’s essential to appreciate the historical momentum that carried the company for decades. The 15-year period from 1985 to 2000 represents the golden age of x86 – and by extension, the Wintel era. During this time, Intel didn’t just ride the PC wave – it helped define it, in concert with Microsoft.

As PC chip revenues exploded, the tight integration between Intel and Microsoft created an unstoppable force as articulated above in Exhibit 2.

- Windows was optimized specifically for Intel chips, and vice versa – Intel embedded instructions into its silicon that Microsoft exploited in software.

- This deep collaboration enabled consistent performance gains and tighter control of the platform.

- Intel surpassed all other semiconductor players, including IBM, becoming the world’s largest chipmaker by 1992.

- Unix RISC vendors – HP, Sun, IBM—responded by going upmarket, seeking refuge in the enterprise as Intel monopolized the PC landscape.

- By 1995, even thought these Unix “open systems” servers overtook older minicomputer price/performance, the broader shift in compute economics was coming up from below with x86.

We believe the secret to the dominance of x86 lies in the flywheel effect of volume, value, and velocity. Intel supplied the volume – economies of scale and manufacturing capacity that no competitor could match. Microsoft delivered the value, with Windows becoming the de facto standard in both consumer and enterprise environments. Together, they removed friction and accelerated velocity across the industry.

This dynamic had a cascading effect:

- The sheer volume of PC chips funded Intel’s data center ambitions, giving it the scale to decimate incumbent Unix systems in the enterprise.

- By the early 2000s, Intel had achieved over 90% share in the data center—a stranglehold driven by x86’s price/performance and an ecosystem that left little room for alternatives.

In our opinion, this period laid the foundation for Intel’s dominance – but also embedded structural dependencies that would later become liabilities. The same tight coupling with Windows, the same x86-centric worldview, and the same centralized design ethos that once propelled Intel forward would later hinder its ability to adapt to changing market forces.

Tim Cook Says “Intel is not a Foundry”

While x86 volumes and margins drove Intel’s ascendancy in PCs and data centers, a quieter disruption was unfolding in parallel. It’s now well understood that what began as consumer novelties – devices like Apple’s iPod – would evolve into a tectonic platform shift that Intel failed to capitalize on. ARM’s architecture, with its low power consumption and efficient instruction sets, was tailor-made for the mobile era. Apple recognized this early on. When Intel passed on competing for the design win, Apple selected ARM with its superior battery life and thermals as key differentiators. The iPhone’s success would soon validate that choice and eventually bleed into PCs and the enterprise.

The broader ecosystem followed suit as described in Exhibit 3 above:

- Apple chose ARM for the iPhone architecture, and subsequently rejecting x86 in its PC lines.

- Samsung was initially tapped as the iPhone’s foundry, but later became a direct competitor, prompting Apple to seek a new supplier.

- Apple entered negotiations with TSMC, led by Morris Chang, who ultimately secured the business.

- Notably, Intel was given the chance to bid, not just for designing the iPhone chip, but also to manufacture it. According to accounts by Morris Chang, Tim Cook privately told him in 2011 something to the effect of “Intel just does not know how to be a foundry”.

Our research suggests that Intel’s pass on Apple smartphones wasn’t just a product decision – it was a strategic failure rooted in institutional inertia. Moreover, our sources at the time suggested that Apple gave Intel some number of months to develop a plan to manufacture iPhone chips, at least giving it a possible angle to participate in the new volume play. Apple rejected the bid, reportedly because of Intel’s lack of customization and service capabilities in its foundry.

Intel Ignores the Importance of Unit Volumes – Arm Sweeps in to Win the Day

This wasn’t the first opportunity Intel missed, but it was arguably the most consequential. Former CEO Paul Otellini would later admit it was a mistake to pass on the original iPhone chip design, a decision that left long-lasting damage. In our opinion, this moment marked a generational turning point.

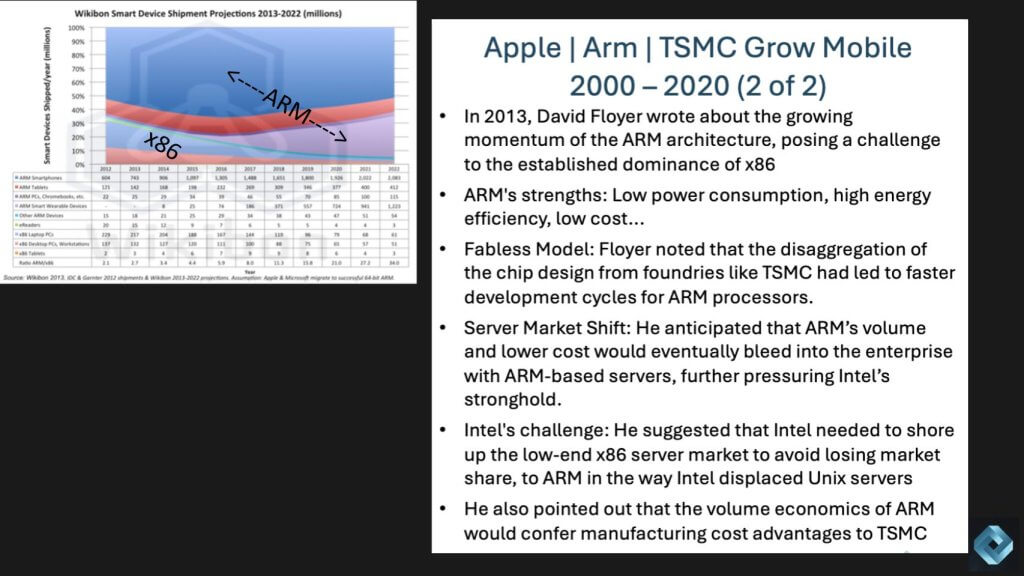

We believe the core issue was that Intel misunderstood the strategic importance of volume, despite that very same volume advantage that allowed it to crush RISC-based systems in earlier decades. ARM’s gains were initially dismissed because they didn’t show up in revenue or profit – but volume conferred learning cycles, developer traction, and economies of scale. These advantages mirrored Intel’s own rise decades earlier, yet the company failed to recognize the parallel.

As early as 2013, David Floyer warned that mobile volumes would overwhelm x86’s dominance, just as x86 once toppled minicomputers and mainframes. That prediction – once considered premature – now appears prescient. Even by that time, ARM-based silicon had already surpassed Intel in unit volumes as shown in Exhibit 4 above. Despite this, Intel took no decisive action. The company that once prided itself on paranoia and performance leadership had, in effect, lost its sense of urgency.

COVID’s Mirage and the Peak of x86 – Arm Quietly Invades the Enterprise

As the mobile revolution accelerated outside the data center spotlight, few in the enterprise took it seriously. Many analysts became sanguine and sometimes fixated on Intel’s continued strength. x86 had long since vanquished RISC Unix systems in the server market, and with the rise of cloud computing, Intel’s market position only seemed to harden. From the dot-com era through the 2010s, Intel rode a powerful wave – that to some looked, if not unshakable, still promising. Below in Exhibit 5 we recount this history.

That illusion would persist until COVID exposed structural flaws.

From 2000 to 2020, Intel executed a bottom-up invasion of the data center:

- Leveraging PC volumes, it entered the server space at scale, even though its chips weren’t initially optimized for data center workloads.

- Linux adoption during the dot-com boom accelerated migration off proprietary Unix systems and simplified the transition to x86.

- Intel displaced RISC vendors like HP, IBM, and Sun, eventually capturing an estimated 95%+ share of the server CPU market.

- x86 became the default for cloud computing, with hyperscalers standardizing on Intel-based infrastructure.

This momentum carried into the 2010s, but signs of trouble began to appear. Major cloud providers, particularly AWS, started looking for ways to reduce dependence on Intel. Initial trials with AMD failed to displace x86, but Amazon eventually turned to internal development through Annapurna Labs. The birth of the Graviton processor marked a strategic pivot – away from x86 and toward Arm.

Still, none of this was widely seen as a threat by many analysts. Then came COVID.

The pandemic triggered a surge in PC demand as remote work took hold. Volume spiked. OEMs like Dell experienced a jump in PC revenue. And many, including Intel leadership, misread the signal. Some believed this uptick represented a sustainable resurgence in x86 demand. But it was a temporary anomaly – a final burst of relevance.

- PC sales surged, pushing x86 revenue to an all-time high of $88B in 2020, a peak that has not been matched since.

- Analyst estimates and internal forecasts misjudged the durability of these volumes, believing the remote work trend would sustain elevated demand.

- Dell’s revenue data during the period, while strong, supports the view that 2020–2021 was the high-water mark, not a new normal.

In our view, this period was a mirage for Intel – masking underlying erosion in the company’s strategic position. The same volume flywheel that once catapulted x86 forward had reversed. Mobile and ARM-based architectures now held the growth leveer, while Intel clung to a temporarily inflated market.

The parallels to IBM’s past are striking. Just as Big Blue failed to respond to the rise of lower-cost CMOS designs and was encumbered by mainframe inertia, Intel failed to respond to Arm’s volume and efficiency lead. In both cases, success bred complacency. And as history reminds us, only the paranoid survive.

History Rhymes: From IBM’s Fall to Intel’s Reckoning

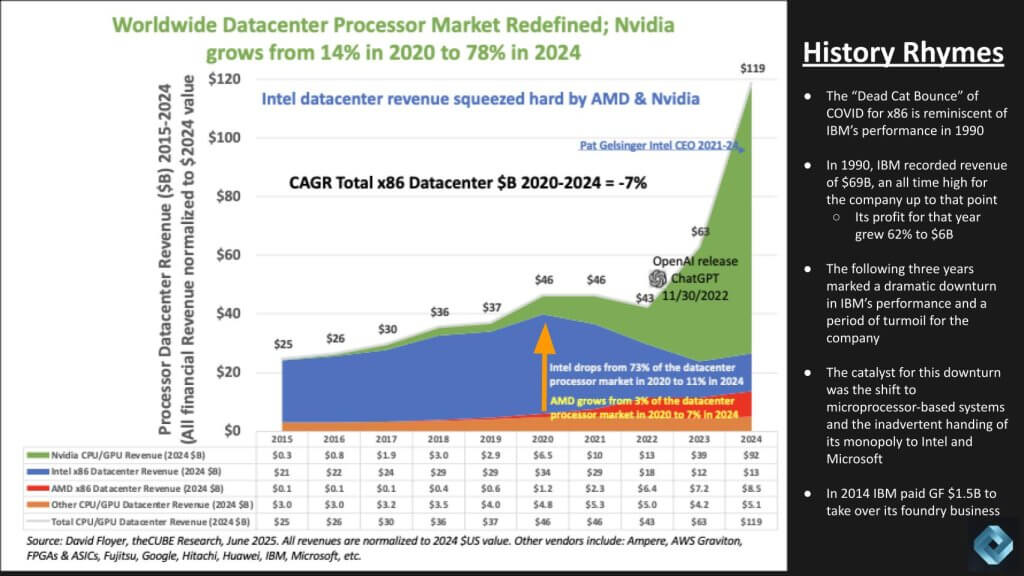

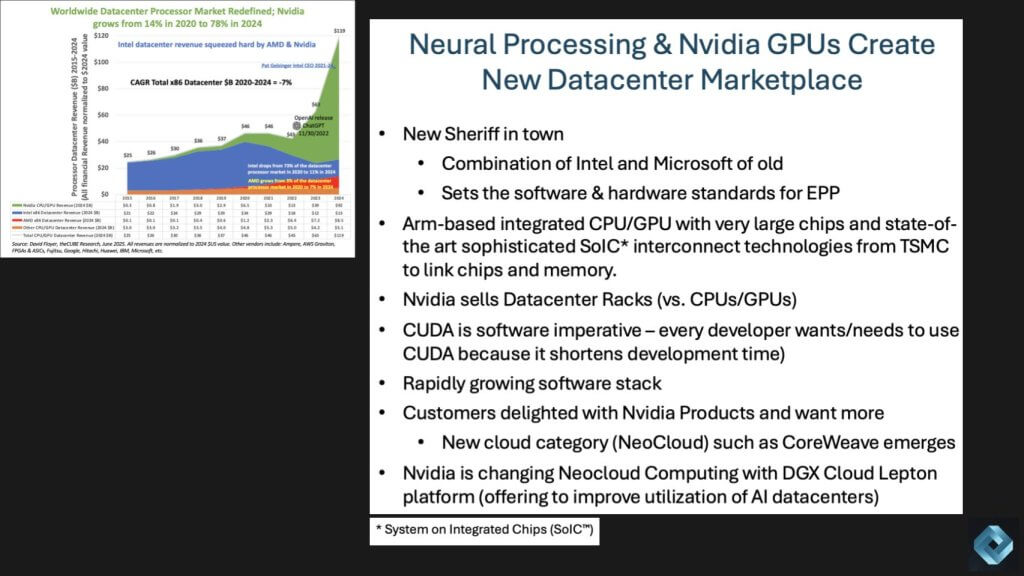

Intel loses sixty-two percentage points of data center processor share in four years.

In the wake of COVID, the illusion of x86’s staying power evaporated – not only in PCs but in the data center as well. As highlighted in the Exhibit 6 below, Intel’s data center revenue has suffered a sharp and sustained decline, squeezed from below by AMD and from above by NVIDIA. Between 2020 and 2024, Intel’s share of the data center processor market dropped from 73% to just 11%.

This moment, in our view, echoes a pivotal chapter in tech history: IBM in 1990.

- In that year, IBM hit record revenue of $69 billion and profits soared by 62%. On paper, it looked like the company was thriving.

- But the seeds of disruption had already been planted. The rise of microprocessor-based systems eroded IBM’s dominance in proprietary hardware.

- Over the next three years, IBM experienced the most painful decline in its history – financial losses, failed restructuring plans, and an identity crisis that culminated in spinning off its semiconductor manufacturing business two decades later.

- In 2014, IBM paid GlobalFoundries $1.5 billion to take its Microelectronics division off its hands.

We believe the same forces are now playing out with Intel – just inverted. Intel was once the disruptor, unseating IBM by embracing x86 and riding the volume economics of PC chips. But it has now become the incumbent being disrupted, this time by a new compute paradigm – so-called accelerated computing.

The catalyst was the launch of ChatGPT in late 2022, which unleashed a torrent of demand for AI workloads. The traditional scalar processing model that underpinned x86 is ill-suited for AI inference and training at scale. In contrast, NVIDIA’s GPU-based architecture – what we refer to as extreme parallel processing (EPP) – has emerged as the ideal foundation for generative AI.

- NVIDIA’s share of data center processor revenue surged from 14% in 2020 to 78% in 2024.

- Intel’s x86 data center revenue declined at a -7% CAGR over the same period, despite the overall market nearly tripling in size.

- AMD, while a smaller player, also grew its share from 3% to 7%, further compressing Intel’s footprint.

We see this as more than a cycle – it’s a complete market reset. What’s different this time is that the shift isn’t just to faster or cheaper chips. Rather it’s a move to a fundamentally different architecture, better suited to the AI era. Traditional scalar processing is giving way to parallel. General-purpose CPUs are ceding ground to domain-specific accelerators. And the dominant suppliers of the past are being replaced by platform companies optimized for the future.

In short, where Intel once rode the rise of microprocessors to dethrone IBM, it now faces a similar fate – overtaken by a new architecture, a new set of economic drivers, and a new dominant monopoly in the form of NVIDIA.

Foundry Economics Expose Intel’s Dilemma

Much of our concern around Intel centers on its ambition to become a world-class foundry outside of its own captive production. The company has publicly committed to regaining process leadership and serving external customers at scale. Yet the economic realities suggest this is a monumental challenge – one that history tells us is extremely difficult to overcome without unlimited capital and time.

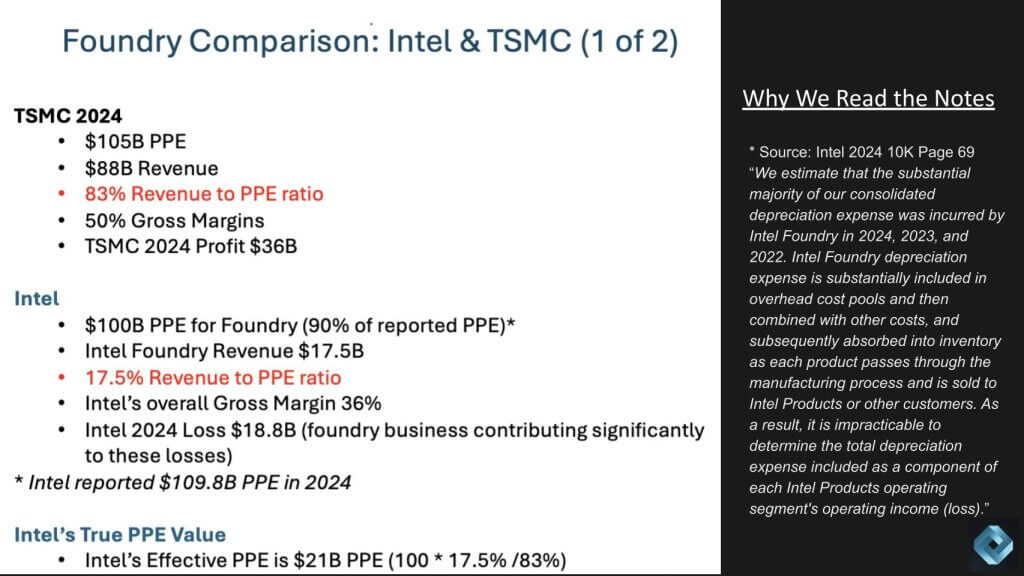

The data in Exhibit 7 below paints a stark contrast between Intel and TSMC:

- TSMC 2024: $105B in plant, property, and equipment (PPE); $88B in revenue; 83% revenue-to-PPE ratio; 50% gross margins; $36B in profit.

- Intel 2024: $100B estimated PPE for foundry; $17.5B in foundry revenue; just 17.5% revenue-to-PPE ratio; 36% overall gross margin; $18.8B net loss.

We believe the key indicator here is revenue efficiency. Intel’s foundry is producing just 21 cents of revenue per dollar of PPE investment, using TSMC as the benchmark. That suggests nearly $80 billion of Intel’s capital base is underutilized, with little prospect of near-term profitability.

According to Intel’s own 10-K disclosures, the vast majority of depreciation expense is tied to the foundry business. While difficult to isolate, this underscores the scale of the challenge – an asset-heavy, capital-intensive business that is currently delivering negative economic value.

Our view is that this economic disconnect was one major reason Intel has been unable – or unwilling – to pursue more aggressive structural moves, such as spinning off its foundry or forming a joint venture with TSMC. There is a reluctance to acknowledge that, on a GAAP basis, the foundry likely represents negative value.

This dynamic mirrors what IBM faced when it paid GlobalFoundries $1.5 billion to take its microelectronics business. No board wants to repeat that headline. And yet, without a drastic rethink, Intel’s balance sheet may remain saddled with unproductive assets.

That said, not all hope is lost.

Former Intel executive Diane Bryant, who led the data center business during its peak, offered a candid yet cautiously optimistic view. She acknowledged that Intel has tried and failed five times to build a viable foundry business. But she expressed confidence in current CEO Lip-Bu Tan’s leadership, noting that while catching up to the leading edge is extremely difficult, not all chips require the most advanced nodes. There is still value in legacy and trailing-edge capacity—particularly for IoT and industrial applications.

We agree with that view, but we also see the risk. Betting on lagging nodes may keep fabs full, but it won’t position Intel to compete with TSMC or Samsung on the most advanced innovation cycles. And while the CHIPS Act may provide some near-term funding relief, it won’t alter the structural economics without fundamental changes in execution.

In our opinion:

- Intel must right-size its foundry ambitions to match the market reality.

- A national security argument for domestic manufacturing is legitimate – but it’s not a business model on its own.

- The leadership transition provides a potential inflection point, but a full recovery could take a decade or more.

At best, the foundry journey remains a long road with uncertain returns. At worst, it’s a repeat of a painful chapter in U.S. semiconductor history. Under Lip-Bu Tan our current base case is that Intel will dramatically cut costs, continue to write off assets, compete for N-1 and N-2 process business, remain far behind TSMC but ahead of foundries like Global Foundries from a node perspective. We believe it has a 40% chance of becoming a viable foundry for external customers over the long term and a 60% chance of being forced into a more radical change such as IBM faced in 2014. If China invades Taiwan, it could dramatically change these odds in ways we’ll discuss later in this research note.

The New Datacenter Paradigm: NVIDIA Sets the Standard

As the world now knows, a new sheriff has emerged in the datacenter – and its name is NVIDIA. The torch once held by Intel and Microsoft as the defining force in compute has now been passed to a different kind of duo – i.e. NVIDIA, CUDA, its libraries, digital twin software and growing ecosystem. In many ways, this new architecture mirrors the dynamics of the Wintel era, with NVIDIA combining hardware and software into a de facto standard for the accelerated computing age.

We believe the post-ChatGPT surge in demand has only solidified NVIDIA’s position as the dominant force shaping the datacenter future. The company is now doing what Intel once did – re-defining the stack as described in Exhibit 8 below.

Consider the elements of NVIDIA’s new playbook:

- Combines ARM-based designs with massive chips and advanced packaging, leveraging cutting-edge interconnect technologies from TSMC.

- Delivers full systems – not just chips— – with NVIDIA selling entire datacenter racks and offering DGX Cloud through partners.

- Owns the software layer through CUDA, which has become indispensable for developers due to its ability to shorten time-to-insight and optimize performance.

- Enables a new class of cloud providers, dubbed NeoClouds, with companies like CoreWeave, Lambda, Genesis, Caruso and others emerging to meet AI-specific demand.

- Continues to expand its stack, from networking to memory to management software, creating lock-in and differentiation well beyond silicon.

What’s more, NVIDIA’s position is not simply the result of better hardware – it’s the integration of software, systems, and developer mindshare that has built a formidable moat. CUDA has become the new x86 – i.e. a language and platform every AI developer must understand and use. The growth of NVIDIA’s installed base means its APIs, libraries, and protocols are now the default.

This dominance is reinforced by high-profile validation. As noted recently, even Elon Musk has committed to using NVIDIA over alternatives, citing performance and ecosystem maturity as key reasons.

From our vantage point, this shift represents a wholesale restructuring of the datacenter value chain:

- The old model, where OEMs built commodity x86 boxes and layered in software after the fact, is being replaced by vertically integrated systems tuned for AI.

- The new model prioritizes performance-per-watt, system integration, and time-to-deployment—areas where NVIDIA now leads.

We believe any player hoping to compete must align to this new reality. Whether it’s storage vendors like VAST, or silicon hopefuls like Intel, the future will be defined by how well they integrate with the NVIDIA-centric ecosystem – and/or differentiate meaningfully from it.

NVIDIA has become the new standard bearer. And unlike previous cycles, it’s setting the rules at both the hardware and software levels. In our view, tee opportunity for others lies not in displacing NVIDIA outright, but in carving out niches of differentiated value within the AI supply chain.

The Future of x86: A Managed Decline

The x86 era is not ending tomorrow – but its place in the computing hierarchy is undeniably shifting and far less relevant. As shown in Exhibit 9 below, between 2019 and 2024, x86 revenues declined at a 6% CAGR. And our current forecast indicates an even steeper slide of 13% annually through 2025 for traditional workloads. This decline is structural, not cyclical.

The rise of AI has created a new datacenter marketplace, one where general-purpose CPUs are increasingly taking a back seat to AI-optimized architectures. The market for what we call AI Extreme Processing – largely GPU-accelerated, cloud-native, and highly parallel – is projected to grow at a 26% CAGR. By the end of the decade, we believe this new segment will be four times the size of the traditional x86 compute market.

In this new world:

- NeoCloud providers like CoreWeave are deploying NVIDIA-based systems built explicitly for AI, leaving no room for Intel and others to play a meaningful role without a differentiated AI offering.

- Intel specifically has virtually no presence or proven credibility in this space. It lacks the rich ecosystem, the design wins, and the trust of AI-native buyers.

- In x86, AMD is outpacing Intel – using TSMC to deliver higher core counts, greater power efficiency, superior memory bandwidth, and best-in-class gaming performance.

- Gelsinger’s strategy, had it been fully funded and executed, may have bankrupted Intel, according to our analysis. It would have required massive investment with uncertain ROI. LBT has taken the reigns and is on a more practical, albeit less ambitious path.

- LBT’s strategy is more measured, but it still faces enormous questions. How long will it take to restore competitiveness? Can Intel break through in AI? And will its foundry bet ever deliver meaningful external traction?

In our view, the x86 market has now entered what we’d call a “managed decline” phase:

- AMD and Intel may continue to make solid products.

- They may even stabilize share relative to one another.

- But the category itself is shrinking and being outgrown by a new paradigm.

The most likely scenario is that x86 continues to serve legacy workloads, particularly in enterprise, client, and embedded use cases. But the new innovation cycles – especially in AI and next-gen data platforms – will increasingly exclude x86 in favor of architectures purpose-built for extreme parallel processing.

We believe Intel and AMD would do well to maximize the value of their x86 franchises while investing selectively in areas where they can add differentiated value – particularly where performance, latency, or governance create competitive moats. We’ll explore this in more detail in the next section of this note.

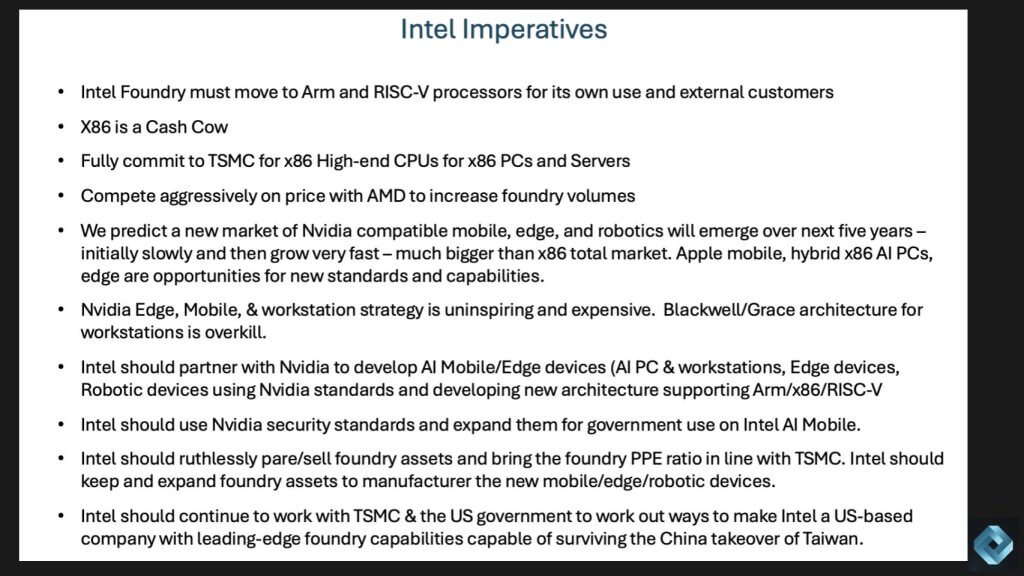

Intel’s Imperatives: From Delusional to Defensive Posture to Strategic Rebuild

Given its declining share in data center compute, mounting foundry losses, and missed opportunities in smartphones and AI, Intel now faces a critical juncture. The future success of the company will depend not on a return to past dominance, but on embracing a different role – one that prioritizes pragmatism, integration with broader ecosystems, and selective leadership in emerging markets.

Our research suggests a focused, multi-pronged approach is essential as described in Exhibit 10 above:

- Embrace wafer-scale volumes by pivoting the foundry toward Arm and RISC-V designs. Intel’s foundry must serve not just captive x86 demand, but the broader universe of alternative architectures. We believe its product business must also explore these areas to differentiate at the edge, for inference workloads and emerging robotics opportunities.

- Treat x86 as a cash cow – and manage its costs. Continue monetizing it while minimizing investment in legacy platforms.

- Use TSMC for advanced x86 PC and server products to remain competitive with AMD. There is no shame in partnering with the world’s best foundry – only strategic advantage in doing so.

- Compete aggressively with AMD on price to increase utilization of foundry assets, even if it means lowering margins temporarily.

Looking ahead, the biggest opportunities may lie not in data center, but in AI PCs where no vendor has the advantage, at the edge and in robotics.

We predict a major new market will emerge over the next five years – i.e. NVIDIA-compatible mobile, edge, and robotics platforms. While slower to ramp initially, this segment has the potential to exceed the x86 PC market in both volume and value. Here, Intel has real assets – experience with low-power design, longstanding government relationships, and embedded x86 ecosystems that can be extended or bridged into hybrid platforms.

But seizing this opportunity requires alignment with the dominant AI platform – NVIDIA. But in a way that differentiates from NVIDIA where it is not dominant to avoid becoming a lower priced, lower margin “plug compatible” designer.

- Intel should adopt and extend NVIDIA’s standards, including CUDA and emerging security frameworks, particularly for military and government use cases.

- Partnering with NVIDIA on edge and mobile designs could give Intel a foothold in a market where Blackwell and Grace architectures are likely overkill.

- Focus on smaller systems – AI PCs, robotics, edge devices – where efficiency, cost, and ruggedization matter more than raw FLOPs. This is a wide open market and one that NVIDIA has not dominated.

- Develop hybrid chips and system architectures that support ARM/x86/RISC-V and are optimized for NeoCloud standards and environments.

- Cater to the existing Intel developer ecosystem to support the new direction.

Internally, the company must take aggressive action:

- Ruthlessly prune underperforming foundry assets, improving PPE efficiency and utilization.

- Work closely with TSMC and U.S. government stakeholders to ensure Intel remains a viable, sovereign supplier in the event of geopolitical disruption.

In our view, this path forward won’t recapture Intel’s former glory – but it offers a realistic, value-creating trajectory that aligns with both market trends and national interests. The key will be humility, focus, and a willingness to integrate into ecosystems it no longer controls.

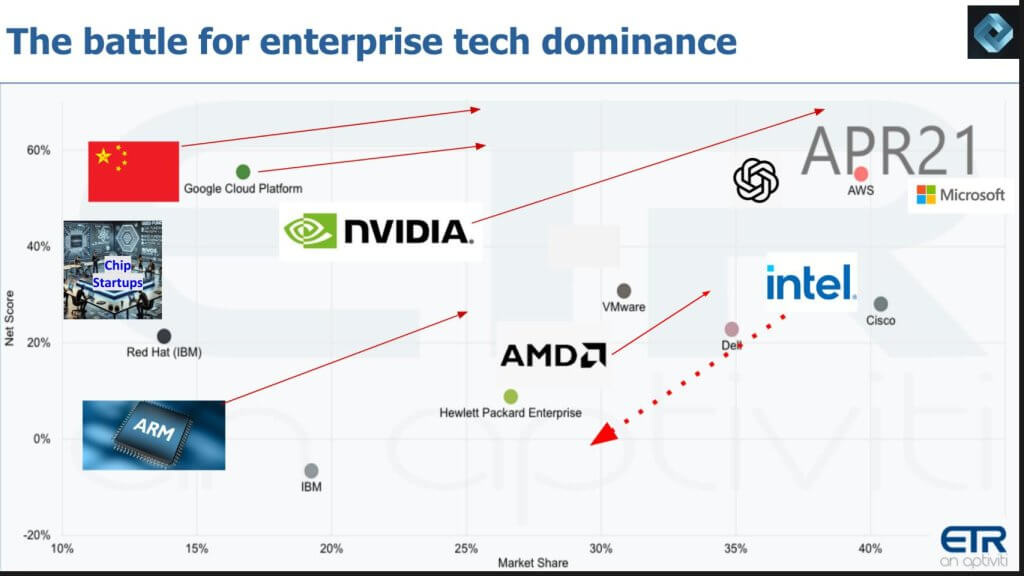

A Missed Opportunity to Secure U.S. Semiconductor Leadership

As we close, we revisit a chart first presented in April 2021 to forecast the coming battle for enterprise tech dominance. We present it as Exhibit 11 below with some arrows to update the changes since that time. Though the chart predates ChatGPT and the generative AI explosion, many of the directional themes have come to pass. NVIDIA has moved decisively up and to the right, becoming the undisputed leader in data center innovation. Arm is rising on the back of its increasing ubiquity and the flexibility the fabless model has created. AMD has effectively swapped places with Intel in x86 strength. And China’s ambitions loom larger than ever.

What hasn’t changed – but should have in our view – is the U.S. approach to semiconductor sovereignty.

The reality is stark in that Intel’s foundry ambitions remain years away from bearing fruit. Even under optimistic scenarios, it will take the better part of a decade for the company to establish even line of site parity with TSMC’s leading-edge capabilities. In parallel, U.S. policymakers and tech leaders have failed to back a bold, actionable plan to secure domestic chip manufacturing at scale – one that could survive geopolitical disruptions in East Asia. In particular, the U.S. is relying on the hope that TSMC will build advanced semiconductor manufacturing capabilities on shore and bring the requisite talent and IP to create foundries on par with its Taiwanese facilities. We see this as highly unlikely and essentially a capitulation to cede manufacturing leadership to Asia.

Pat Gelsigner’s ambitions were not misguided, rather his path to success was virtually impossible without unlimited money and time. And it appears the U.S. government has given up on the ambition to have a U.S. domiciled and headquartered firm that develops the most advanced chips. We believe this is a mistake that will come back to haunt the United States.

Let’s consider the consequences of a China-controlled Taiwan:

- If China takes over TSMC, it gains leverage over the world’s most advanced semiconductor IP and production capacity.

- Even if TSMC builds plants on U.S. soil, it’s unlikely those fabs will ever match Taiwan’s leading-edge output. At best, they’ll be N-minus-one or N-minus-two.

- The U.S. would find itself in a weakened negotiating position – forced to secure access through diplomacy, tariffs, or worse, with severe implications for military readiness and economic competitiveness.

This is not a far-fetched scenario. Xi Jinping has publicly stated reunification with Taiwan is inevitable. Should that happen in the next three to five years – as Intel is still restructuring and ramping its foundry – America will be left without a domestically headquartered, bleeding-edge chip supplier.

We believe this represents a critical failure of both industry and government.

- The U.S. should have moved more decisively to back a spinout or joint venture of Intel Foundry – leveraging capital from hyperscalers, sovereign interests, and NVIDIA to create a new national champion.

- Intel, for its part, refused to recognize the possibility of negative value in its foundry assets, opting instead to preserve optionality – and control.

- As history shows with IBM and AMD, these decisions are often delayed until economic or competitive pressure forces a divestiture. By then, the strategic window may be closed.

Some argue that the U.S. doesn’t need a leading-edge domestic champion – that TSMC’s Arizona investments are sufficient. We disagree. In our view, it is vital that the U.S. not only have advanced manufacturing capacity onshore, but that it is owned, operated, and innovated by a U.S.-domiciled entity. Without that, America risks falling behind in the very arms race that will define this century – AI.

We close with this – There is a race underway – not just for compute, but for control of the future. A future where AI capabilities shape economies, militaries, and societal outcomes. And while the U.S. still leads in many respects, it cannot afford to forfeit control of the most strategic layer of the technology stack.

Intel had the chance to lead that effort. It may still have another with the help of the most powerful country in the world. But the clock is ticking.