Two prevailing narratives have driven markets recently. The first is that NVIDIA’s moat is eroding primarily due to GPU alternatives such as TPUs and other ASICs. The second is that Google generally and Gemini specifically are gaining share, will dominate AI search and ultimately beat OpenAI. We believe both of these propositions are overstated and unlikely to materialize as currently envisioned by many. Specifically, our research indicates that NVIDIA’s GB300 and the follow-on Vera Rubin will completely reset the economics of AI, conferring continued advantage to NVIDIA. Furthermore, NVIDIA’s volume lead will make it the low-cost producer and, by far, the most economical platform to run AI at scale – for both training and inference.

As it pertains to Google, it faces, in our view, the ultimate innovator’s dilemma because its search is tightly linked to advertising revenue. If Google moves its advertising model to a chatbot-like experience, its cost to serve search queries goes up by 100X. The alternative is to shift its business model toward a more integrated shopping experience. But this requires more than 10 blue links thrown at users. Rather, it mandates a new trust compact with its users and advertisers, which Google does not currently possess, even with Gemini’s recent success. Despite the criticisms of ChatGPT, OpenAI, in our estimation, is well on the way to disrupting today’s online experience by emphasizing trusted information over pushing ads. The bottom line is that the two early catalyzers of the AI era, NVIDIA and OpenAI, remain in a strong position in our view. While lots can change, the current narrative around these two firms is likely to change when GB300 adoption ramps.

In this, our 300th Breaking Analysis, we set forth our thinking around what we believe is a misplaced narrative in the market. We’ll explain what we think the market is missing and why NVIDIA’s forthcoming product lineup will reset the narrative. We’ll also look at the economics of search, LLMs, and chatbots and share why OpenAI, while facing many challenges (competition, commitments, uncertainty), is in a stronger position than many have posited; and why Google, while clearly a leader in AI, remains challenged to preserve what may be the greatest business in the history of the technology business.

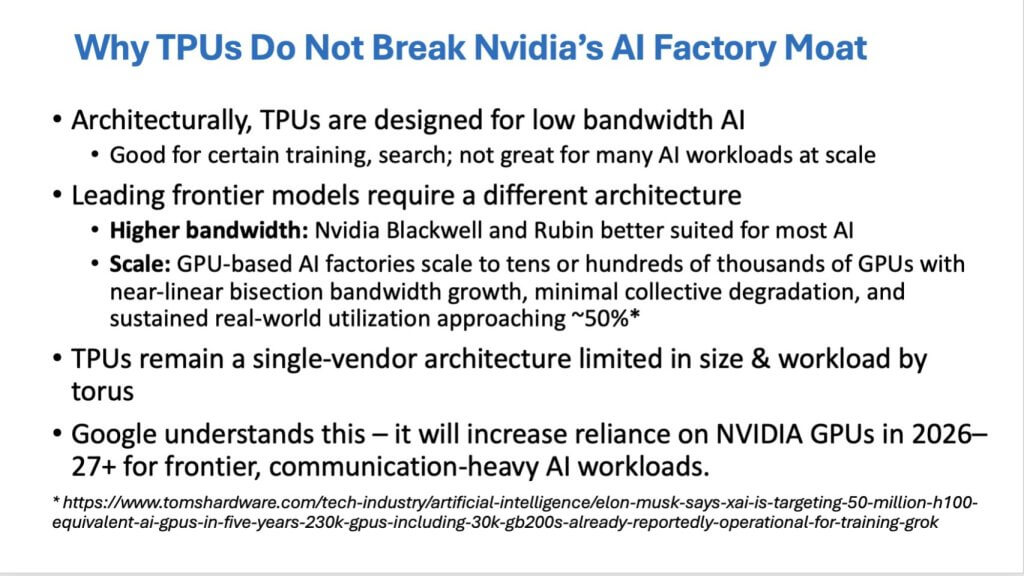

Why TPUs don’t break NVIDIA’s AI factory moat

We believe the core issue with TPUs isn’t whether they’re “good” chips — they are. The issue, in our view, is broad-based architectural fit for the next phase of AI, where frontier-scale workloads are increasingly communication-heavy, bandwidth-hungry, and require systems that can scale to very large clusters without collapsing under their own coordination overhead. In our assessment, TPUs were designed in an era when bandwidth was expensive and hard to deliver, and that design center shows up as models scale and workloads diversify.

What TPUs were built for — and where the ceiling shows up

TPUs are well-suited for lower-bandwidth AI and have proven effective in production contexts such as search. They can do certain training well, and they’ve been associated with important early milestones. But as models get larger and the work becomes more distributed, our research indicates the TPU design runs into practical constraints on expansion and on the amount of bandwidth available within the architecture. In our view, that’s a key reason the TPU approach hasn’t become the broadly replicated blueprint across the industry.

Why frontier training looks different than “TPU-friendly” workloads

We believe leading frontier efforts increasingly demand an architecture optimized for high bandwidth and scale — the kind of system design that enables “GPU factories,” where very large numbers of accelerators can be connected and kept productively utilized.

When we talk about the requirements for AI factories, we highlight below three key factors:

- Near-linear bisection bandwidth growth: Bisection bandwidth is essentially the throughput across the “middle” of the network — how much data can move between two halves of the system. As workloads become more complex and more distributed, the system needs that cross-fabric bandwidth to grow smoothly as you add more devices.

- Minimal collective degradation: As you scale out, collective communication patterns can become the bottleneck. The system has to avoid performance falling off a cliff as more nodes participate.

- Sustained real-world utilization (~50%): The goal isn’t theoretical peak. It’s keeping the system doing useful work at scale, consistently, in production-like conditions.

In our view, architectures designed around higher-bandwidth, scalable interconnects are better aligned with those requirements.

The “single-vendor pod” constraint

Our premise is that TPUs remain a single-vendor architecture with a topology that effectively forms pods — a tightly coupled unit presented as a single system. That approach was elegant for its time and echoed other historic designs (e.g., IBM Blue Gene, Cray) intended to solve the “how do we connect everything” problem. But we believe the limitations show up in two places:

- It doesn’t scale the way frontier workloads increasingly require;

- It doesn’t deliver the net bandwidth needed for the most communication-heavy, frontier-class model development.

None of this makes TPUs irrelevant. In our opinion, TPUs remain extremely useful and attractive — particularly for more bounded workloads — but usefulness is not the same thing as being the dominant foundation for next-generation AI factories. And in our framework, it’s definitely not the platform that will erode NVIDIA’s moat.

The market narrative is oversimplified

We believe the popular storyline — “Model X is trained on TPUs, therefore TPUs are the future” — misses the reality. Our view is that some major model training has indeed leveraged TPUs, but the data points toward a mixed approach where GPU-class architectures become increasingly necessary for frontier-scale, communication-heavy work.

Our research indicates there’s also a pragmatic factor. Specifically, when accelerators are constrained, it’s rational to push existing assets to their limits. In that context, using available TPUs aggressively is not a statement that TPUs are the end state — it’s an optimization under supply constraints.

Key takeaway

We’re not bearish on TPUs. They are mature, and the engineering behind them is impressive. But we believe NVIDIA’s moat is reinforced by an end-to-end architecture designed for bandwidth, scale, and sustained utilization — the attributes that matter most as AI factories move from impressive single-system demos to large-scale production infrastructure.

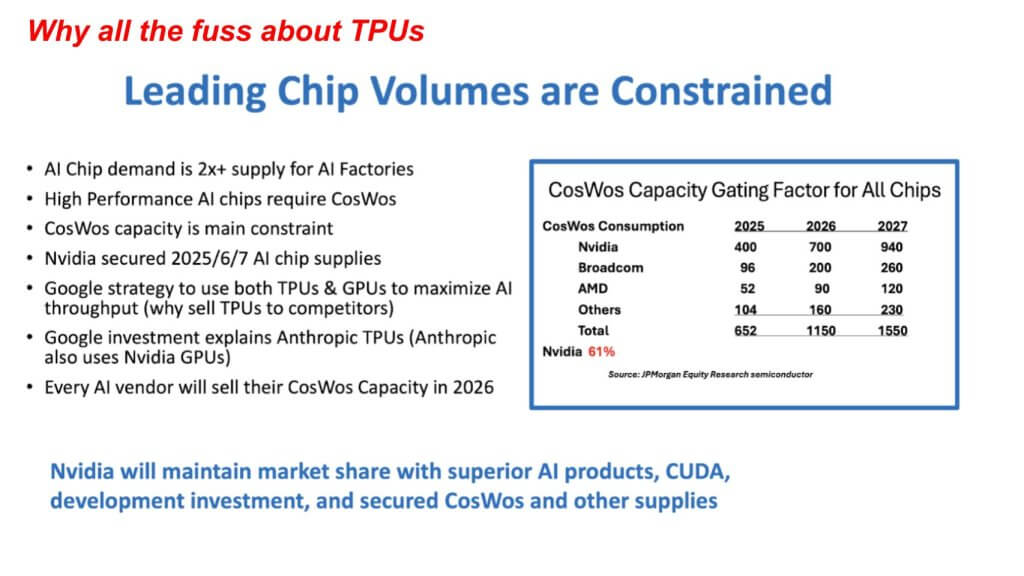

Why all the fuss about TPUs? Supply constraints, CoWoS, and the market reality

We believe the recent TPU enthusiasm is less about a structural shift away from NVIDIA and more about the fact that volumes are constrained, demand is outstripping supply, and every hyperscaler is operating under scarcity. In this environment, buyers and builders will use whatever credible compute they can get — and that dynamic is amplifying the availability and capabilities of TPUs, as well as other alternatives.

CoWoS is the gating factor

The biggest constraint our research points to right now is packaging capacity. CoWoS (chip-on-wafer-on-substrate) is a TSMC packaging technology that takes chiplets from the wafer and integrates them onto a substrate so they can be connected with very high-speed communication. In our view, this is foundational to modern AI systems that depend on fast movement between chips and across complex multi-chip architectures.

The key point is that when CoWoS capacity is tight, it constrains the output of advanced AI accelerators regardless of how strong demand is.

What the CoWoS consumption chart tells us

The chart above shows projected consumption across NVIDIA, Broadcom, AMD, and others — and importantly, it reflects all chips, not only AI chips. That matters because portions of the non-NVIDIA consumption are serving other product categories and process needs. But the bottom line remains that AI chips are being governed by the same packaging bottleneck.

In the data referenced, total CoWoS capacity expands materially over time with NVIDIA locking up more than 60% of the volume:

- 2025: 652

- 2026: 1150

- 2027: 1550

At the same time, the compute and system efficiency of the leading platforms improves as NVIDIA transitions through architectural steps — from GB200 to GB300 and then Rubin — alongside improvements in switching and overall system design. In our opinion, the market should view these trends in tandem — i.e., capacity increases, but so does the performance per system, which reinforces the economics for the vendors that can both secure volume and move fastest down the experience curve. The leading vendor, by far, in this scenario is NVIDIA.

NVIDIA’s prebuys translate into share and cost advantage

We believe one of the most underappreciated points in the current narrative is that NVIDIA has effectively pre-bought and secured meaningful CoWoS capacity. As a result, even as the pie expands, NVIDIA is positioned to maintain significant share over the planning horizon discussed — with the projection that by 2027 it still holds roughly 61% of the referenced market. For AI chips specifically, our estimate is that NVIDIA will maintain closer to ~80% of the market.

Our view is that share will be determined by unit economics. Our premise is that NVIDIA has volume leadership and has locked up a critical bottleneck input, which will confer structural cost advantage and flywheel effects to the company.

Why hyperscalers are mixing architectures

In a supply-constrained environment, hyperscalers will pursue a blended strategy. In the case of Google, it will use TPUs where they fit and GPUs where they’re required to generally maximize access to any capable compute. We believe that’s what’s driving much of the current TPU buzz — not a belief that TPUs will broadly displace GPUs for frontier-scale, communication-heavy workloads.

We also believe it’s unlikely that a major hyperscaler (Google in this case) will broadly sell its proprietary accelerators to direct competitors in a way that creates a real external market. Claims and rumors may circulate, but in our opinion, the more plausible driver behind “TPUs in the wild” narratives is ecosystem pressure from partners (e.g., Broadcom) and Meta (looking for any advantage right now). In short, we don’t see this as a strategic decision by Google to become a true merchant silicon provider.

Volume matters, and it compounds into cost leadership

We believe the most important takeaway from this segment is the connection between the following three factors:

- Volume leadership (which has always mattered in semiconductors and other scaled markets);

- Experience curve benefits (learning, yield, supply-chain leverage, system tuning); and

- Control of constrained inputs (CoWoS capacity being the prime example).

In our view, this combination positions NVIDIA, with near-term platforms such as GB300 and especially Rubin, to become the low-cost producers of tokens versus alternatives — not simply because of peak-performance claims, but because scale and secured capacity will translate into superior economics.

The shortage won’t last forever — but it’s not ending tomorrow

We believe the market is in a phase where every credible AI vendor can sell everything they can build because supply is scarce. But our research indicates this will change as capacity catches up over the next couple of years. Historically, semiconductors tend to swing from undersupply to oversupply — timing this is hard, but our research suggests there is still meaningful runway, and that the near-term (including 2026) remains supply-constrained rather than surplus-driven.

Net Net: TPUs are getting attention because the market supply is short. CoWoS is a core bottleneck. And NVIDIA’s ability to lock up capacity and ride the experience curve reinforces both share and cost position as the cycle matures.

A recent investor podcast, Gavin Baker, went deep into the economics of GPUs and TPU. It’s worth listening to the entire conversation. We pulled a clip from that discussion that succinctly articulates the pending economic shift coming in the near term.

What follows is our assessment of that conversation blended with our premise:

Low-cost production, learning curves, and why the advantage is shifting back to NVIDIA

We believe the “low-cost producer” framing is critical, but it’s often misunderstood and not applied rigorously. In our view, being the low-cost producer has always mattered in scaled markets — the nuance is whether people mean unit cost, delivered price, or economic margin structure. When viewed through that perspective, Google’s position as the current low-cost producer for AI chips is increasingly fragile as the stack shifts and as the economics of TPU/ASIC supply chains become more clear.

Google’s current cost position is real — but not sustainable

Our research aligns with Gavin Baker’s narrative, which indicates Google has enjoyed meaningful cost advantages in parts of its AI stack and has leaned into that position by aggressively approaching the market. Google can “bomb” AI with low-cost capacity because when you can drive lower unit costs, you can push more supply into the market and press competitors on price and availability.

But we believe that advantage is highly dependent on the underlying performance curve and the economics of the hardware supply chain — and both are moving.

Blackwell as an industry learning platform

We believe one under-appreciated structural advantage for NVDIA is the learning loop created when a major deployment runs infrastructure at extreme scale. In our view, large-scale Blackwell deployments — particularly the kind of “push it to the limits” rollout that X.ai is driving — act as a forcing function that exposes bugs, tightens systems performance, and accelerates resilience. NVIDIA learns from this and then propagates those learnings across its customer base, which translates into a time-to-market advantage that is difficult for alternatives to match unless NVIDIA stumbles operationally.

In our opinion, this dynamic will compound as scale finds issues faster, fixes get distributed broadly, and the platform improves as more customers run it in production-like conditions.

Scaling laws are intact — and that raises the premium on throughput and efficiency

Gemini 3, as Baker points out, has demonstrated that the scaling laws are still working. Our research indicates that, if scaling continues to pay off, then the market’s center of gravity shifts toward whoever can deliver the most training and inference work per dollar, per watt, and per unit time — at scale.

That’s where NVIDIA’s roadmap is positioned to reassert its dominance, as GB300s are drop-in compatible with GB200. The delta from Hopper to Blackwell was non-trivial. We’ve previously reported the lower reliability of GB200-based racks due to new cooling requirements, rack densities, and the overall complexity of the transition. But early reports suggest GB300-based configurations at neoclouds are performing exceptionally well, with low friction for upgrades from GB200-based infrastructure. This compatibility accelerates deployment velocity and improves the probability that customers stay on the NVIDIA upgrade path rather than detouring into architectural forks.

And the economics favor NVIDIA.

TPU economics: The Broadcom dependency inherent in margins

We believe the economics of the TPU/ASIC stack are often overlooked. A critical constraint is if a large portion of value accrues to a supplier (e.g., Broadcom as Google’s ASIC partner), then the “low-cost producer” claim becomes more complicated. Gavin Baker estimates that at scale, roughly $15B of Google’s $30B TPU revenue goes to Broadcom, which eats a major share of the margin pool. Baker used a simple analogy that Google is like the architect and Broadcom is the builder — it manages the TSMC relationship. He correctly points out that Apple has taken control of both the front-end design and all the backend work, including managing TSMC, because at its scale, that level of vertical integration makes sense.

This dynamic puts pressure on Google’s behavior over time. Even if TPU unit economics look attractive in isolation, the supplier margin structure can erode the sustained ability to undercut the market — especially as NVIDIA’s performance-per-system improves. Baker stated that the OPEX for Broadcom’s entire semi division is $5B, so at scale, Google paying Broadcom $15B may become less attractive.

Rubin widens the gap

We believe the roadmap implication is that GB300 will reset the cost curve, and if Rubin extends it again, the space between NVIDIA and TPU/ASIC alternatives increases dramatically. In our opinion, that doesn’t make TPUs irrelevant; it makes them situational. As NVIDIA’s platform becomes a lower-cost token producer at scale, alternatives are forced into narrower lanes or into “use what you have” strategies.

NVIDIA vs. Google/Broadcom and Seagate vs. Quantum/MKE

This topic is reminiscent of a battle in the disk drive business in the 1980s. Seagate was a leading manufacturer of hard drives at the time and pursued a vertically integrated strategy, manufacturing its own heads, media, and the drives themselves. In the 1980’s, Quantum was a player struggling with manufacturing quality, but revived its business by outsourcing production to MKE, a world-class Japanese-based manufacturer. While this required tight engineering coordination between designers and manufacturing, it addressed Quantum’s “backend” challenges. Quantum began to rapidly gain share, and its stock price rose.

This author, in a conversation with industry legend Al Shugart, CEO of Seagate, asked if this was a new business model that had merit. Shugart said simply, “When you have to pay someone to make your product, you make less.” He further intimated that long-term, when the industry consolidated, he would be the last man standing. At the time, there were around 80 hard drive manufacturers; today, there are three, with Seagate as the most valuable.

Battle of the LLMs

There’s a tight linkage between silicon and models. In this next section, we move further up the stack and examine the recent narrative around Google, Gemini, and OpenAI.

Looking forward: Models converge and services differentiate

Our research indicates the competitive battle is moving up the stack. While there’s excitement about the rapid improvement in model capability — and we believe larger, more complete models will continue to emerge as AI factories ramp — a key strategic premise of ours is that model quality alone won’t be the enduring differentiator. In our view, the center of gravity shifts to:

- The software ecosystem;

- The services wrapped around models; and

- The ability to operationalize those models reliably and economically.

As laid out above, even if Google can claim periods of cost advantage today, we believe NVIDIA’s platform learnings, drop-in upgrade path, and performance roadmap — combined with the margin realities embedded in TPU supply chains — shift the “low-cost producer” advantage back toward NVIDIA over the next two cycles and likely beyond.

The Gemini user-growth narrative misses the real setup: Google’s innovator’s dilemma

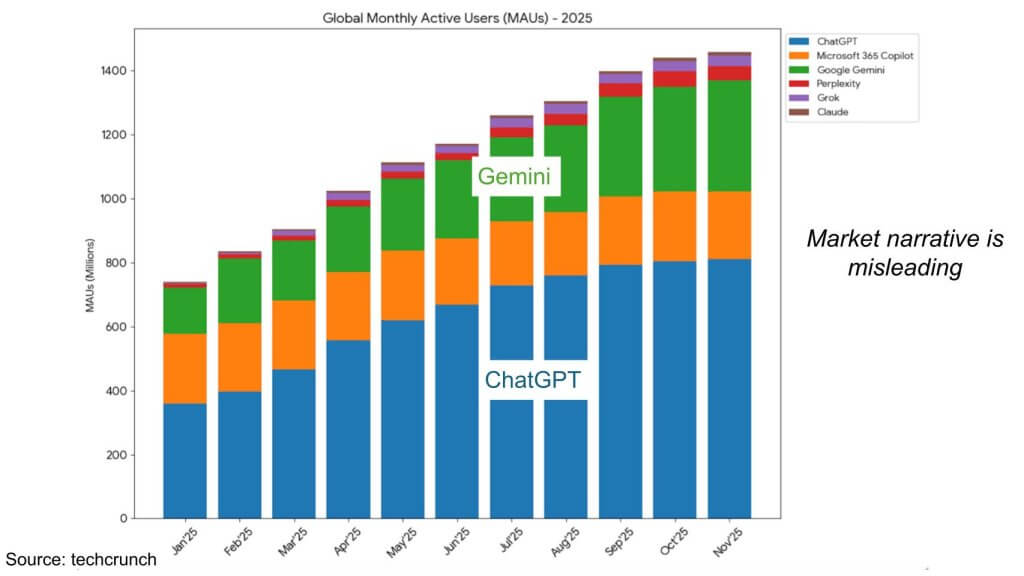

We believe it’s fair to say Gemini 3 has had a meaningful impact on the AI conversation, particularly in reinforcing that scaling laws remain intact. But we also believe some of the widely circulated charts — especially those implying ChatGPT is “leveling off” while Gemini is “exploding” — are potentially misleading if they’re used as a proxy for durable competitive advantage or for what matters most economically.

Why the MAU charts can distort what’s happening

Our view is that user growth charts are easy to over-interpret because they compress very different distribution mechanics into a single line. A product can appear to “explode” in monthly active users due to bundling, defaults, integration points, or placement — while another can appear to “flatten” even as usage quality, monetization, and ecosystem affinity remain strong. The data suggests there’s more nuance here than the headline narrative implies.

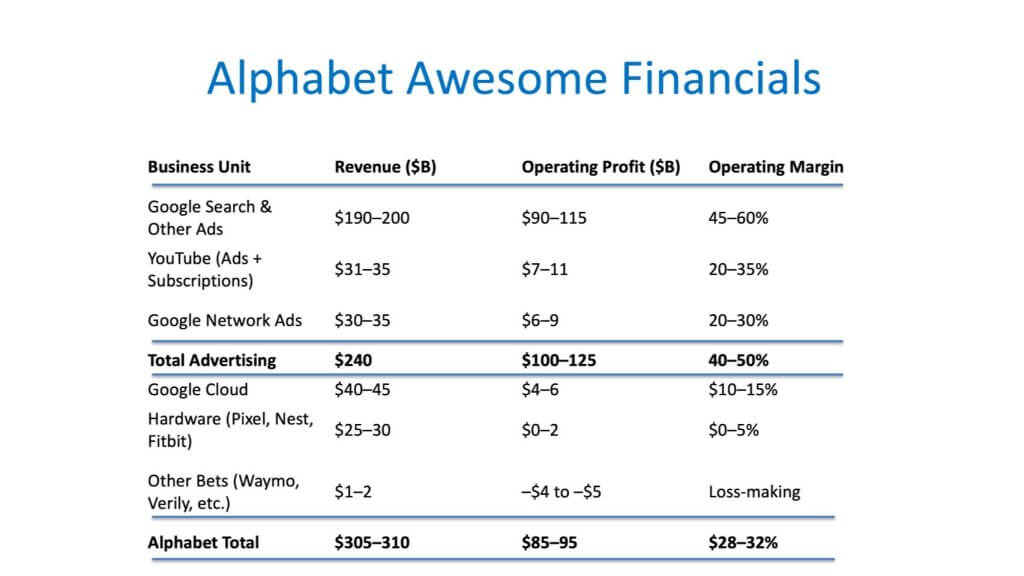

The real context: Google is fundamentally an advertising profit engine

The more important factor, in our opinion, is that Alphabet’s economic center of gravity is still advertising — particularly Search and related advertising properties. As shown below, Google generates an enormous amount of operating profit from advertising, with very large operating margins.

Cloud, while meaningful in absolute dollars and improving in profitability, is still minor relative to the scale of Search-driven operating profit. Even at rising operating margin levels, the cloud business is small compared to the hundreds of billions in operating profit and cash generation tied to the advertising machine. And the “Other Bets” category is economically immaterial in the context of the overall profit engine.

This creates a classic innovator’s dilemma

Google has arguably the world’s best technology marketplace in the form of Search — extraordinary query volume, an unparalleled advertising monetization model, and a highly efficient compute foundation that reinforces profitability. The system works, and it works at massive scale.

The dilemma, in our view, is how Google migrates from that dominant model to something “more complete” without undermining the profit engine that made it dominant in the first place. The data suggests the challenge is not whether Google can build strong AI models — it clearly can. The challenge is whether it can evolve the product and business model of Search in a way that preserves economics while moving toward a new interaction paradigm.

What to watch

Our strategic questions for Google are:

- Can Google transition from its current search-and-ads model to a more complete AI-native experience without cannibalizing the very margins and monetization dynamics that fund its advantage?

- Can it do that while maintaining the operating discipline and low-cost compute foundation that make the existing machine so powerful?

Gemini’s momentum is impressive, but we believe the larger story is economic and structural. Google’s strength in search creates the very dilemma it has to solve to lead the next phase.

Engagement, not just MAUs: Why “user minutes” changes the economics of AI + ads

We believe the earlier monthly active user charts tell an incomplete story that can be misleading if used to infer leadership or monetization power. The more instructive view is engagement as shown above. Specifically, the Similarweb data shows user minutes on the web — because time spent is a better proxy for intensity of use, dependency, and ultimately monetizable opportunity.

ChatGPT’s lead shows up more clearly in user minutes

ChatGPT maintains a meaningful lead in user minutes, even as Gemini is growing quickly. The chart also shows fast growth from other entrants (e.g., DeepSeek and Grok), but in our view the competitive reality remains concentrated and it’s primarily a two-horse race for the bulk of user attention between ChatGPT and Gemini.

The key metric is not only “who is growing,” but who is capturing time.

Why minutes matter more than “users” in the advertising context

We believe the implications become more acute when you overlay Google’s economic model. Google’s profit engine is built on advertising monetization tied to search behavior — high volume, low marginal cost, and well-optimized conversion funnels. That machine depends on serving an enormous number of ad opportunities efficiently.

But if the interaction model shifts toward ChatGPT-style experiences — richer answers, longer sessions, and more compute-heavy responses — the cost structure changes dramatically.

The compute cost of richer answers is the problem

Our research indicates each unit of engagement in an assistant-style model is materially more compute-intensive than the classic search model. The point made above is for a comparable “user minute,” the assistant model can consume on the order of ~10x more compute resources to generate substantially richer output for the end user.

In our view, this is the crux of why merging an AI assistant interaction model with an ad-funded business model is not trivial:

- In classic search, ads are served into a low-cost query/response sequence;

- In assistant-led experiences, the same user attention requires far higher compute, which raises the cost of each monetizable interaction.

So while an AI-native interface may create a more compelling product, it also risks turning the economics of ad delivery from a high-margin machine into a heavier-cost model — unless monetization mechanics evolve to compensate.

Even “user minutes” still understate what’s happening

We believe user minutes are a better metric than MAUs, but they still don’t fully capture the true shift. Time spent doesn’t directly measure the quantity and richness of knowledge being produced and delivered into the market — and that richness is precisely what drives the compute intensity.

The bottom line is engagement is the right metric, but the deeper point is economic. If the market moves from low-cost search interactions to compute-heavy assistant interactions, the cost to serve — and therefore the cost to monetize — rises sharply. That’s the pressure point for Google’s ad-dominated business model in our view.

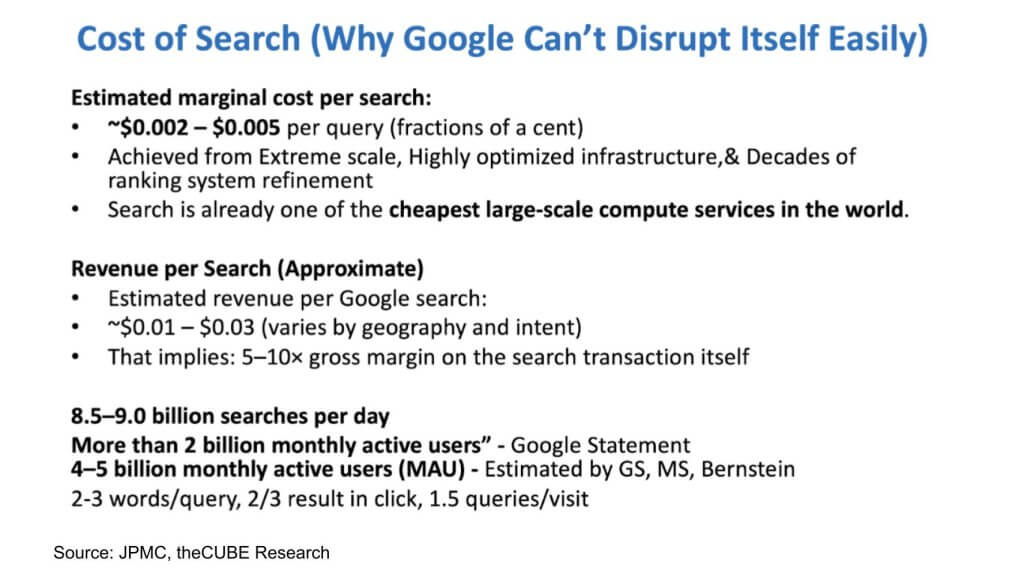

Why “Google will just disrupt itself” is not a casual decision: The unit economics of search are changing

We believe a common refrain, “Google will just disrupt itself,” ignores the single most important constraint, in that the economics of Search are uniquely favorable to Google, and moving from classic search to an assistant-style interaction model changes the unit economics in a way that can break the profit engine.

Search is an extreme-scale, ultra-optimized compute business

Our research indicates the cost of a search is a fraction of a cent. That outcome is the product of:

- Decades of ranking system refinement;

- Extreme scale; and

- A highly optimized infrastructure stack.

In our view, this is arguably the cheapest large-scale compute service in the world, and among the best-operated at a global scale.

The margin structure is the moat — and it’s hard to walk away from

The point is that revenue per search is ~5x to 10x the gross margin on the cost of the search itself. That’s the heart of the extraordinary business model Google has built — ultra-low unit cost paired with a monetization engine that extracts high value per interaction.

In our opinion, you don’t casually disrupt a model with those economics — not because you lack vision, but because the alternative must clear a very high economic bar.

The workload characteristics are simple — and that’s the advantage

Our research indicates the nature of search queries supports these economics:

- Roughly 8–9 billion searches per day;

- Billions of active users;

- Queries are typically very short (often two to three words);

- Two out of three searches result in a click;

- About 1 to 1.5 queries per visit.

This is a high-volume, low-complexity workload. It is optimized for speed, efficiency, and monetization — not for generating richly reasoned outputs.

Turning search into an assistant collapses the model unless monetization changes

Our central claim is that if Google converts this ultra-cheap interaction into an OpenAI-style experience — richer responses, longer sessions, higher compute per interaction — the cost structure rises sharply. If cost per “search” increases by an order of magnitude while monetization mechanics remain in the old ad model, the economics compress and the business model can break.

The bottom line is Google can absolutely innovate, but the data indicates self-disruption is economic surgery. The existing search machine is optimized around simplicity and margin. Shifting to compute-intensive assistant behavior without a new monetization model risks collapsing the very engine that funds the transition.

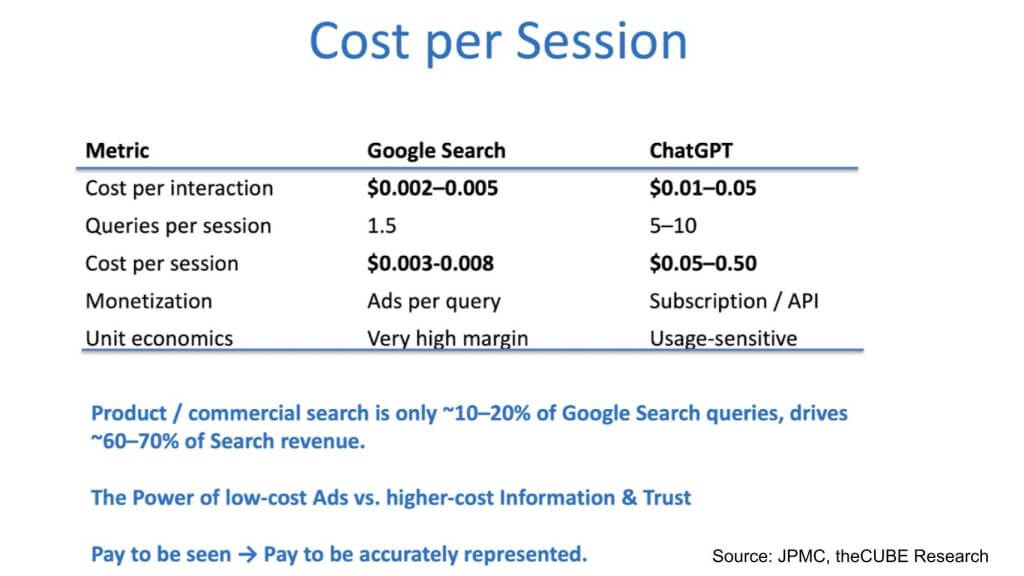

Cost per session is the economic tripwire for Google’s self-disruption

The debate about whether Google can disrupt itself becomes much clearer when you model cost per session rather than looking at top-line user counts. As indicated, the economics of classic Google Search are engineered around extremely low cost per interaction and very high-margin monetization. Assistant-style sessions invert that equation.

Google Search: Pennies per session, high-margin ads per query

Our research indicates the cost per interaction for Google Search is in the range of roughly 0.2 to 0.5 (as presented on the slide above), and because queries per session are low, the resulting cost per session is still “less than pennies.” The monetization model is also tightly coupled to this structure in that Google monetizes with ads per query, and the combination of low cost + strong ad yield produces very high margins.

In our view, this is why Google Search has been such a durable business model. It is a highly optimized, low-cost service that is monetized efficiently at massive scale.

ChatGPT-style sessions have a fundamentally different cost structure

ChatGPT’s cost per interaction is much higher, and the session pattern is different, with 5 to 10 queries per session rather than the short, lightweight search interactions. When you multiply those factors, the cost per session becomes dramatically higher — we think ~100x higher than Google Search.

Importantly, the point is not that ChatGPT is inefficient. The claim is that ChatGPT is already among the leaders in efficiency — yet the underlying interaction paradigm is still much more compute-intensive per session.

We believe this is the core reason Google can’t simply flip Search into a ChatGPT-like model without destabilizing margins.

The “10–20% / 60–70%” problem: The revenue concentration makes this existential

Our research indicates the most economically valuable portion of search is product and commercial search — only ~10–20% of queries, but responsible for ~60–70% of search revenue. In our view, that concentration is exactly what makes the transition so difficult. Specifically:

- This slice is the pie Google most needs to protect;

- It is also the slice most likely to be contested as AI assistants move upstream into higher-intent workflows.

A profound shift in how monetization works: From “pay to be seen” to “pay to be accurately represented”

We believe this is one of the most important ideas in the entire research note. The model moves from low-cost ads and blue links thrown at users toward a higher-value, higher-cost information economy where trust and accurate representation are the products.

In our view, this has two direct implications:

- Brands become far more sensitive to information quality than to link placement.

- Monetization migrates from “pay for visibility” toward “pay for verified, trusted, high-fidelity representation” — a different commercial construct with different economic models.

What happens to Google’s “hybrid” mode?

Google’s current approach — offering a hybrid path where users can go deeper into AI mode — is both clever and useful. In an ideal world, Google would prefer to introduce assistant-style experiences slowly, ring-fence them as a separate business, and price them at a premium.

But the point is that reality constrains the strategy because Google has to protect the commercial-search numbers. And while Google would like to layer higher-value services on top and charge advertisers materially more, it may be easier for challengers to enter with higher-cost, higher-trust services without needing to defend a legacy margin structure. This, we believe, is OpenAI’s advantage.

That tension makes the hybrid model look less like a stable end state and more like a transitional strategy — a fence-sitter that ultimately has to resolve toward one economic model or the other.

Framing the competitive battlefield

In our view, the market is carving into two distinct conflicts:

- Nvidia vs. TPU/ASIC alternatives: Relatively clear to us, barring execution missteps;

- Google vs. OpenAI (and others): Far less clear, because it is a battle over interface, economics, and trust — not just model quality.

The bottom line is that the cost per session is the economic forcing function in this new game. It explains why self-disruption is difficult, why the high-value commercial slice is vulnerable, and why the market may shift from cheap ad inventory toward higher-cost, trust-based representation. This is the battle line for the next decade.

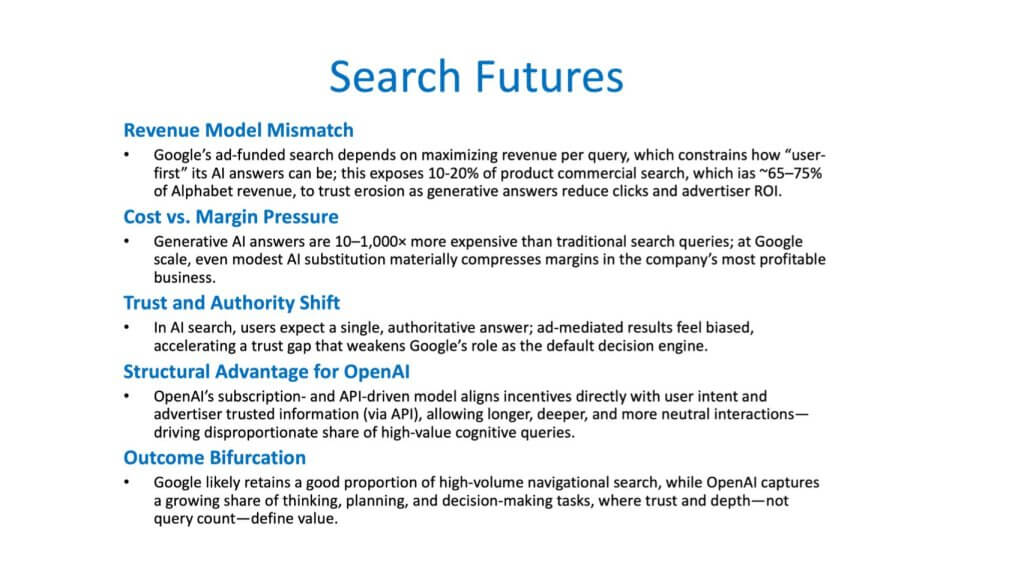

The future of search is a revenue-model mismatch — and the highest-value slice is at risk

We believe the core issue in “the future of search” is not model quality. The issue is a revenue model mismatch. Traditional search is an ad-funded machine optimized to deliver low-cost discovery — effectively “ten blue links” thrown at the user — where monetization is tied to placement and clicks, not to the intrinsic quality and trustworthiness of the information delivered.

As search becomes answer-centric and trust-centric, our research indicates a large portion of Google’s profit pool becomes exposed.

A small slice of queries drives most of the money — and it’s easy to lose on trust

In this research, we try to make a concentrated revenue point that we believe is the linchpin:

- ~10–15% of queries are commercial/product-intent;

- That slice contributes ~65–75% of search revenues.

In our view, this is the part of the business that is most vulnerable to trust erosion. If users begin to believe the answer is optimized for the advertiser rather than for the buyer, the value proposition degrades quickly — and that small slice is exactly where buyers are most sensitive to quality, ranking integrity, and confidence.

The risk is that Google can retain the bulk of total search volume and still lose the economically decisive segment: “90% of search,” but not the part that pays the bills.

GenAI answers are orders of magnitude more expensive — and scale makes it unforgiving

Our research indicates that generating an answer with gen AI is at least an order of magnitude more expensive than a classic, highly optimized search query — and potentially two or three orders depending on the experience design. At Google’s scale, even modest mix shifts toward AI-heavy sessions can have an outsized margin impact.

We believe this becomes both a timing and strategy issue. In other words, the transition begins to bite into margins as usage patterns migrate, and the company has to manage a delicate balance between to countervailing forces:

- Protecting current margins; and

- Preventing leakage of high-trust, high-value queries to other platforms.

From the consumer standpoint, there is an upside in that users can increasingly choose between low-cost traditional search and higher-quality, higher-trust answer engines. But that optionality increases competitive pressure.

Trust and authority become the new switching costs

Because Google’s search share is so highly elevated, it has nowhere to go but down from here, because the competitive axis is shifting. In classic search, if the result isn’t good, the user simply refines the query and continues. In assistant-driven search, as users build affinity for an engine that consistently returns higher-quality outcomes, memory and trust become the moat. The platform that earns that trust can pull a disproportionate share of the highest-value sessions.

The key point is that even if Google’s model quality is strong, the business model incentives are different.

Why this is a different business model, not just a better UI

In our view, the future state is not “smarter ads.” It’s a different value chain where brands need to be represented accurately, compared appropriately, and surfaced based on fit — not on who bought the top slot.

The premise of this research captures the delta: a complex, high-intent request can be satisfied in a single minute with ranked options and an action plan, rather than a longer, more iterative search process. Our research indicates that this “high-quality commercial search” experience is precisely where share can migrate — and it’s the most economically meaningful slice that moves.

OpenAI’s structural advantage: Aligned incentives via subscriptions and APIs

We believe OpenAI has a structural incentive advantage rooted in its revenue model:

- Users pay (often via subscription) because they value the experience quality;

- Developers and businesses pay through APIs that directly monetize usage.

That incentive system is fundamentally different from ad-funded search, where the buyer is not the user, and where brands pay for placement. In our opinion, this creates a more direct “quality to revenue” linkage for the assistant platform.

On the brand side, our research indicates the emerging play is buyer-facing APIs backed by trusted information, designed to score well in answer engines. That is a different marketing and distribution model than classic SEO and paid links.

SEO isn’t dead — but it’s on a glide path down

We believe the right way to frame it is that SEO is not dead, but it will matter less over time. As answer engines mediate discovery and ranking through trust and structured vendor information, the importance of classic SEO mechanics declines.

Likely outcome: Positive bifurcation

Our view is that the market bifurcates in a way that can still look “good” in absolute terms for Google while being strategically disruptive:

- Google keeps a large share of general search volume.

- OpenAI (and others) gain share in high-value, high-trust commercial intent.

Google will fight hard for that high-value slice, but our research indicates that it requires substantial work above the model layer: APIs, software capabilities, interface design, and the surrounding service stack that enables vendors and users to extract real utility from the platform.

Bottom line is the future of search is a restructuring of incentives and economics. The platform that aligns trust, representation quality, and monetization has the advantage in the most valuable part of the market.

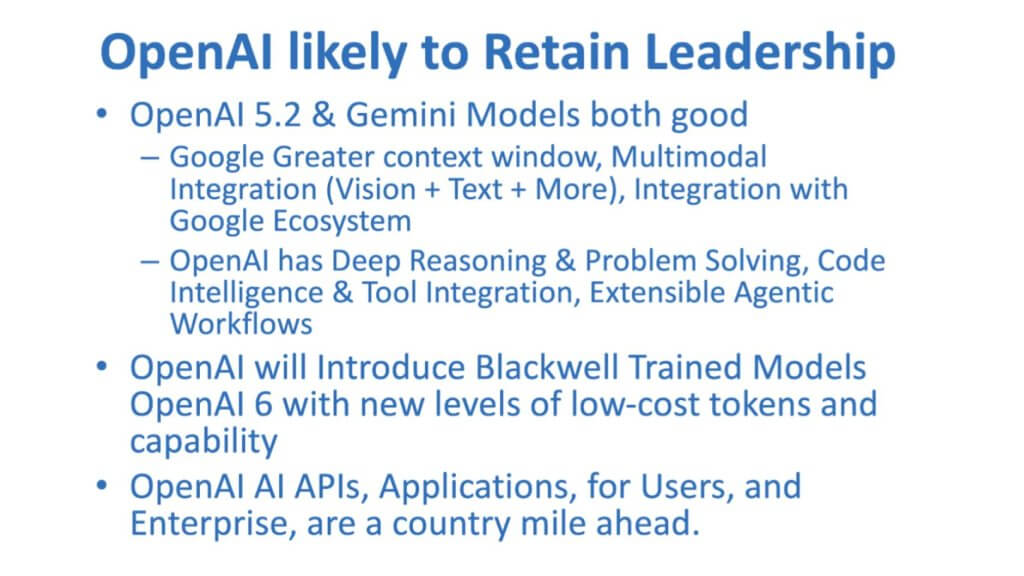

Revisiting the first-mover debate: Why OpenAI’s lead looks durable — and why the enterprise is the real prize

We believe it’s useful to end this segment in the context of an earlier Breaking Analysis in which we put forth a plausible scenario where Google could have disrupted OpenAI’s first-mover advantage. That scenario was not irrational — it was rooted in Google’s deep technical bench, its distribution, and the assumption that it could translate model strength into product and platform leadership.

But the picture on the slide above — “OpenAI likely to retain its leadership” — reflects what our research indicates today: the conditions that sustain OpenAI’s lead are strengthening, not weakening.

The models will converge at the top — so don’t over-index on “best model”

Our view is that the market is over-fixated on model-to-model comparisons. The reality is that the leading labs will all produce very high-quality LLMs. Google’s models are strong. Anthropic’s Claude has positioned around coding. Gemini has demonstrated competence in many tasks, and Grok is moving fast. The point is not that any one of these is “bad.”

We believe the durable differentiation is shifting away from raw model quality and toward:

- The surrounding software stack;

- APIs and developer surface area;

- Applications and workflows;

- The ability to become a default platform for enterprise usage.

OpenAI’s structural advantages: Platform, APIs, and (likely) compute allocation priority

Our research indicates OpenAI maintains leadership in several areas:

- Best APIs;

- Best applications; and

- An overall lead in both users with emerging enterprise momentum.

We also believe OpenAI’s close relationship with NVIDIA matters. Our contention is that if NVIDIA remains the critical supplier for frontier compute, and if OpenAI is tightly coupled to that ecosystem, then OpenAI is positioned to receive preferential allocation versus competitors — particularly versus those whose narrative depends on NVIDIA being displaced. In our view, that allocation dynamic reinforces time-to-capability and time-to-market.

The enterprise mix is shifting

The most important data point in this segment, in our opinion, is the mix shift described between consumer usage and enterprise adoption. We note movement from roughly 70/30 (users/enterprise) last year to about 60/40 by the end of this year.

We believe this is a meaningful signal because enterprise growth tends to be stickier and more platform-defining than consumer novelty. Our research indicates enterprise adoption will increase as organizations learn how to:

- Curate and raise the quality of their data;

- Make that data discoverable and usable by AI systems; and

- Operationalize workflows where trusted information is surfaced reliably.

In our view, that enterprise “data readiness” journey is what turns an AI model into an enterprise system — and that is where platform advantage compounds.

Google has strengths — but software and enterprise positioning remain the question

We believe Google has advantages and will remain a formidable competitor. But our premise is that OpenAI is more likely to emerge as a high-quality software and platform player in enterprise AI than Google, which — despite being strong technically — is not broadly perceived as the enterprise AI software leader.

Our view is that this matters because the next phase of competition is not “who has the best model demo,” but “who owns the workflow and the integration fabric.”

Leadership is not guaranteed — but it’s real right now

Our research indicates OpenAI is “a country mile ahead” at the moment in platform momentum. That does not mean the lead is unassailable. OpenAI could blow up, or competitors could find superior approaches. But as of now, we believe the most likely outcome is continued leadership because the factors that matter most — platform, developer adoption, enterprise mix shift, and access to scarce compute — are currently aligned in OpenAI’s favor.

Closing thoughts

In our view, the two big conclusions of this Breaking Analysis are:

- NVIDIA’s moat looks reinforced by volume, experience curve effects, and years of end-to-end systems work;

- OpenAI’s lead looks reinforced by platform execution and enterprise pull — with a competitive landscape where model quality is table stakes, and the real battle is the software and services wrapped around the model.

The bottom line is that the early “Google disrupts OpenAI” scenario was plausible. But the data and the platform dynamics suggest OpenAI’s first-mover advantage is evolving into something more durable — especially as the enterprise becomes the center of gravity. OpenAI’s relationship with NVIDIA is meaningful. While NVIDIA, like Intel before it, will try to keep the playing field level, for now, it will bolster emerging platforms that are less competitive, such as neocloud players and model builders like OpenAI.