OpenAI’s ChatGPT is widely reported to be the fastest application to 50 million users, easily beating cellphones, the internet, and Facebook to that milestone. But AI is not the only influential new technology that is seeing a sudden spike in adoption.

If you look at what is happening globally, a stronger case can actually be made for the latest generation of digital payment technologies — including the rise of SuperApps in China and Asia, and the debut of Real-Time Payment networks in the developing world and elsewhere. All of these new payment “rails” are growing fast and spreading globally, including to the U.S. and Europe.

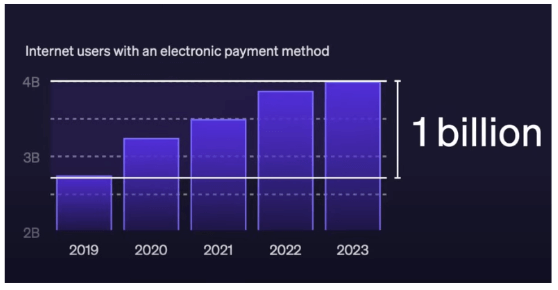

Adding 1 Billion New Users

The global user base for digital payments is now nearly 4 billion users, with a billion of those estimated to be added in just the last five years, according to Patrick and John Collison in their recent keynote at the Stripe Conference:

Watch the full Stripe Sessions Opening Keynote and the Future of Payments session.

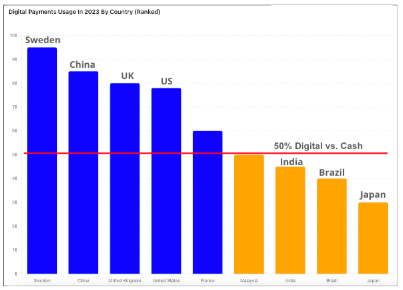

Globally, the use of paper money between buyers and sellers has decreased by 25% in the last decade. In an excellent special report on global finance, published by The Economist in 2023, trillions of dollars of global GDP have since been redirected into digital channels. European countries such as Sweden are almost 90% digital, with China and the U.S. catching up quickly. Likewise, Asian countries such as India, Japan, and Malaysia are soon to surpass the 50% mark.

This migration is also starting to change how governments manage their economies:

- 100s of millions of individuals classified as “unbanked” have moved into the modern financial system, allowing them to build credit history, obtain insurance and get access to interest-bearing accounts and investments.

- At the same time, the role of Central Banks in managing economies is changing. These technologies give them new powers to distribute funds and/or loans directly to citizens or businesses without intermediary layers, or to actively drive down the “hidden tax” of transaction costs maintained by private-sector banks and payment networks.

Disruptions on the Horizon?

The dramatic expansion of the global digital payments economy has been driven by three trends:

- The continued growth of the Bank+Card system in the West

- The rise of SuperApps in China and now extending across Asia

- The introduction of Real-Time Payment (RTP) networks in the developing world

But as this growth evolves, a new competition is brewing as both SuperApps and RTP Networks look to claim a portion of the very lucrative business that the Bank+Card system has built up in the West.

Will the SuperApp Model take off in the West? – Asian SuperApps like Alipay and WeChat have created their own mobile-centric payment networks that perform all the same functions as the Bank+Card system in the West. But they have combined these payment networks with their own consumer-facing brands that appeal to users from the integration of many additional digital services. Would this model work in the U.S. and Europe? If so, which company is best positioned to capitalize on it?

Will public-financed RTP Networks challenge the private sector? – New fast-payment RTP networks based on open-standards and sponsored by governments can potentially perform as well as existing proprietary networks managed by well known brands like Visa and Mastercard, but at much lower cost while also offering a lot more user choice. These networks are growing fast in India and Brazil, and versions of them have appeared in Europe and the U.S. In theory, they could shift a huge a percentage of digital transactions onto public highways, although the private sector is trying to meet this challenge with their own RTP alternatives.

theCUBE Research Perspective

Clearly, the success of SuperApps in China and Asia is a potential harbinger of what is to come in the West. And already Alipay is showing up as a payment alternative next to well-known branded cards on many U.S. e-commerce sites. Not only could they begin to capture payment traffic, they could also capture more Western users directly.

In 2018, Walmart invested $16BN into Flipkart, an Indian SuperApp that is taking advantage of these opportunities precisely because it sees growth in that category. In December of 2023, Walmart invested an additional $600 million in Flipkart, and it was reported the company was in talks at that time to raise an additional $1 billion in funds.

However, it is still not clear SuperApps will succeed in the US. Most likely, it would require a firm with the resources of an Amazon, Walmart, or Facebook to assemble all the components necessary to create a compelling enough experience to drive a broad change in user behavior in the U.S. A wildcard in this category is the Elon Musk effort to rebuild Twitter into something completely new based on his stated WeChat-like ambitions. For a deeper dive on the topic, see this recent article in the Harvard Business Review.

And clearly the RTP networks are creating lots of new opportunities for new B2C and B2B payment brands across the globe. In the West, it is still not clear which form of RTPs will dominate: the “closed” RTPs managed by consortiums of banks (e.g. Zelle, for Swish in Sweden), or more “open” government-sponsored versions like FedNow, which is looking to emulate some of the concepts that have proven successful in India and Brazil. Indeed, a new system could emerge which is a mix of both public & private, much like how the FedACH and TCH EPN system operate in parallel today.

It also remains to be seen if RTP offerings (in either form) can migrate a significant amount of transactions off of the existing Visa/MasterCard networks, or away from the SuperApps in Asia. These firms have created resilient value chains based on the close integration of partners and service providers, and their proprietary networks have already survived the introduction of low-cost debit/ACH alternatives, as well as the arrival of digital wallet apps which try to bypass their systems altogether.

U.S. and Europe Dominated by Bank+Card System

Payment apps and cryptocurrencies have generated a lot of media attention, but the bedrock of the U.S. digital payments system is still by far the Bank+Card architecture driven primarily by the Visa and Mastercard networks, which combined control 87% of the market. Formed in the 1960s and built out in the 1970s, these two firms have used their first-mover advantage as network operators to dominate payment traffic. They have since been joined by smaller networks like American Express and Discover.

They work by interconnecting banks that will participate in their 3-step process of authorization, clearing and settlement. They will then work with those banks to issue specially designed cards for users that will send data over their networks. They make money by taking “swipe fees” from the merchants, but also service fees from the participating banks.

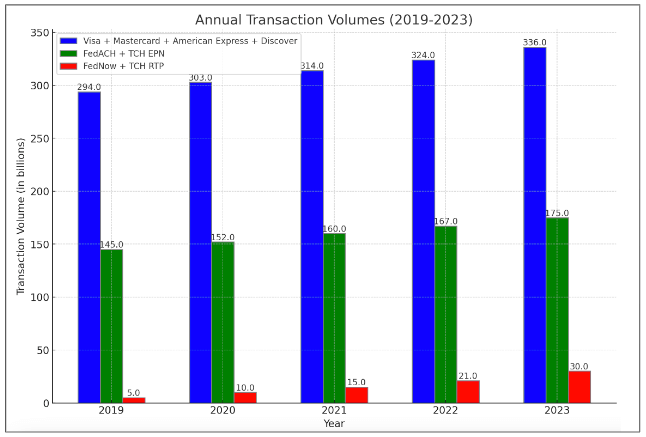

As a result of all these partnerships, the vast majority of U.S. transactions still flow over a small group of select propriety networks that started life before the internet. For merchants, transactions over these networks generally settle faster and with lower settlement risk than most alternatives. This chart shows the relative dominance of these proprietary networks compared their lower-cost rivals, whether the ACH networks or the newer RTP networks.

American Express and Discover operate their own networks similar to Visa and MasterCard, but issue their own cards directly to users. More recently, new types of financial companies like CapitalOne, and apps like PayPal, Square, Apple and Google, have further extended this Bank+Card system by embedding these cards and passing through transactions that settle over these networks. (Of course, wherever possible, these apps try to bypass the networks the leverage the stored value in their digital wallets.)

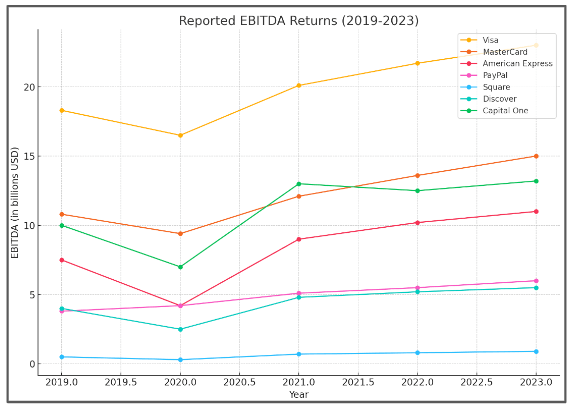

Private Networks Lead to Sustained Profits

Altogether, this Bank+Card arrangement makes for a very lucrative system for the major card issuers, payment apps, and network operators alike, averaging close to 2.5-3% in total transaction fees over the last decade. Fees are generally a mix of interchange fees paid to the issuing banks for processing costs, and then network fees paid to the network operators. These fees have sustained very profitable businesses over time.

For example, between the financial crisis and the pandemic, Mastercard grew its earnings at an extraordinary 10-year CAGR of 20% (compared to single digits for the rest of the S&P 500). 64% of their revenue comes from their network, and the rest are value-add services related to analytics and advisory. In short, they make $0.30 for every $100 that passes over their network.

Most analysts see transactions fees as probably having peaked in the last few years, and likely to now decline due to new pressures — both competitive and legal. Both Visa and Mastercard have become a magnets for anti-trust litigation (see the recent Visa/Mastercard antitrust ruling), and Visa recently settled one of the largest class-action law suits in history.

But for the time being, processing payments on closed, proprietary networks is very profitable. The cost of maintaining the overall network is relatively fixed, so as the volume of transactions climbs then the profitability of each transaction also improves.

Here are some more details on the major players that dominate the Bank+Card system:

- Visa is the largest of the private payment network operators, controlling 60% of the market. It is a digital payments behemoth generating $30BN a year with a market cap of $570BN, with 100 million merchants across the U.S. and Europe, processing 660 million digital payments per day via six private data centers. Its networking operations started life as an association of 1000s banks in the 1970s (lead by Bank of America), which eventually lead to incorporation and an IPO. In 2015, it bought its partner operations in Europe (Visa Europe) for $23 billion and now operates as one company.

- MasterCard is a close second with $20BN in revenue and a market cap of $350BN. It also started as an association of independent banks that pooled their resources in order to compete with BankAmeriCard (later Visa). The majority of its growth has been international, and in particular Europe. Today, it is the most accepted card globally in terms of number of countries.

- AmericanExpress also operates a proprietary payments network, but issues cards direct to its customers rather than working through partner banks.

- Discover also operates a proprietary payments network and issues cards direct to users like American Express, but it functions as complete bank without physical branches

- CapitalOne is also an online bank that issues cards direct to users, but it settles most of its card transactions through existing payment networks rather than operating a competing network

- PayPal, which was an early entrant into wallet-to-wallet transactions, and which also owns Venmo, now also facilitates transactions to the Bank+Card network (through embedded cards) and reports 430 million active users and 80 million of its own merchants, many of which overlap with Visa.

- Square (now Block, Inc.) owns the proprietary Cash App, with 55 million active users, which can either transact through its wallet or pass a transaction through to the card network. It has found success by linking its POS devices for merchants to the CashApp wallet via easy QR codes.

- Stripe has played a key role by accelerating adoption for small merchants with its emphasis on ease-of-use via an aggregator model, which bypasses the need to have individual merchant accounts with banks, and the company is now valued anywhere from $65-$95BN. As of yet Stripe does not have a consumer-facing brand and is still a privately-owned company with an impending IPO thought to be likely in 2025.

China’s SuperApps Dominate the World’s Largest Economy

Different regions of the globe have developed different systems, driven in equal parts by local history and differing levels of government involvement.

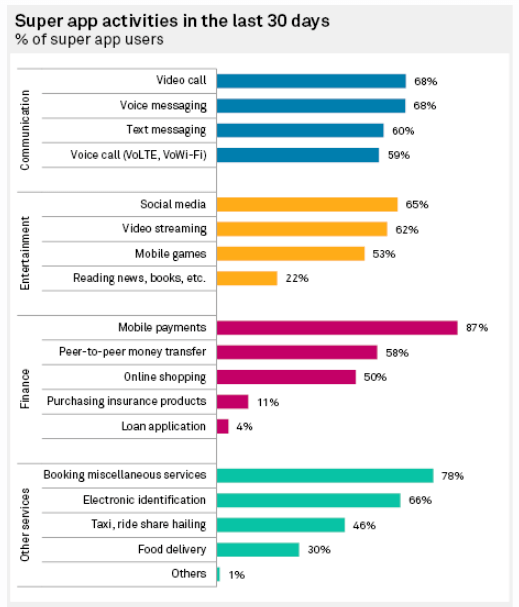

The second part of the global payments story is the rise of the SuperApp system, a collection of multipurpose apps — led primarily by the payment-centric of Alipay (Ant Group) & WeChat (Tencent) — which together control 90% of digital payments in China. Basically they perform many of the same functions that the Visa and MasterCard networks perform in the West, but do it from a mobile-centric perspective. Most user accounts are linked to banks for funding the accounts, just as in the West, but WeChat and Alipay create direct links to the banks themselves (rather than using an intermediary layer), and as such that they can run the pre-authorization and settlement round-trips themselves.

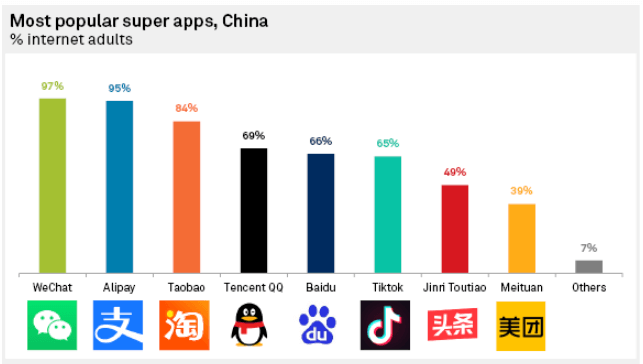

These SuperApps combine a multitude of services — from ride-hailing, to food ordering, to ecommerce — all within one app umbrella, but their core has been payment services, as shown here based on some 2020 survey research summarized in an S&P Global article:

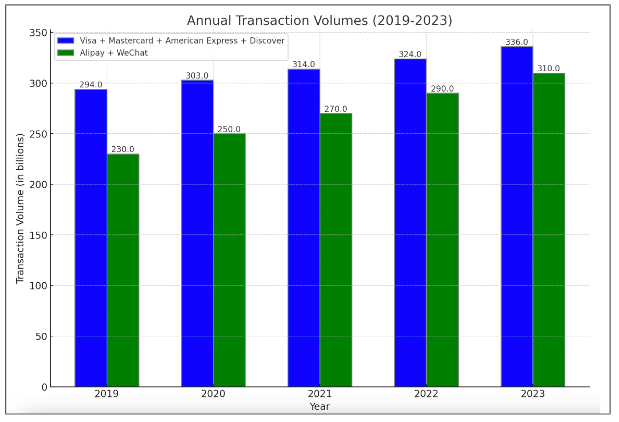

Overall, the level of SuperApp usage for payments is astounding. WeChat and Alipay boast one billion and 800 million users respectively, and in terms of annual payment transactions, the two combined have nearly surpassed the combined Bank+Card system in the U.S.

The success of these apps has now initiated what many perceive as a quasi-government takeover of the firms by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Jack Ma, one of the most high-profile entrepreneurs on the world stage, has since taken a back seat as the government has converted these apps into highly-managed digital payment infrastructure for the entire country. A long the way, they aborted the Ant Financial Group IPO, which would have been one of the largest in history.

As the government has extended its oversight of these apps, the People’s Bank of China in 2002 also set up a new parallel inter-bank settlement system called UnionPay, which is its own type of Bank+Card system very analogous to Visa and MasterCard. Naturally, this new bank network has since been widely integrated with Alipay and WeChat. Taken together, this new combined system very much resembles the overall system in the West.

RTP Networks: A New Standard for Fast Payments

All of these private payment networks, whether card companies in the West or SuperApps in China, settle their transactions relatively fast and with low risk, for which they charge their customers a healthy fee. The alternatives either take longer to settle or cost more to transact. But that is starting to change.

Real-Time Payment (RTP) networks, sometimes called ‘fast networks’ or ‘same day networks’, are a new type of payment network that been architecturally optimized for low cost payments that can settle almost in real time (rather than overnight). These have been facilitated by central banks which run faster batch settlement routines between the accounts of participating banks, typically every two hours.

And the more “open” versions, which have been sponsored primarily by governments, add rules to ensure cross-app compatibility and easy transferability of user identity and personal data between apps. They do this by enforcing a common identity protocol for any user on the network regardless of which app they are using, and a common standard for tokenizing payment information.

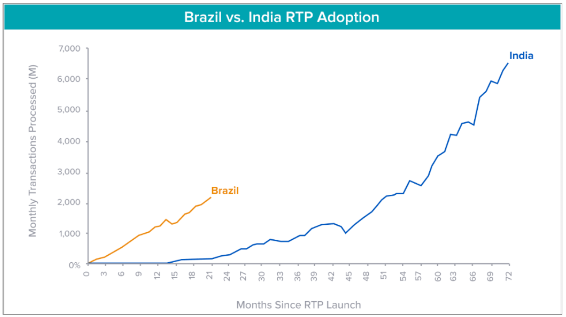

Developed most successfully so far in India, Brazil and Thailand, these new open RTP technology stacks have grown at an exponential rate. The Indian version, called UPI, has tripled its usage since 2019, and is now approaching 300 million transactions per day. Meanwhile, the Brazilian version, called PIX, has grown steadily since its launch in 2020 and is nearing 60 million. A good comparison of the two systems is shown here from the Andreessen Horowitz FinTech newsletter.

In India, UPI stands for Unified Payments Interface (UPI), and is designed as an interconnect layer that allows any user to send funds to any other user of any other app that sits on that network or “rails” as well as transfer personal data and history from app to app, etc.

The National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI) which manages the system, is mandated to ensure extremely low transfer fees, usually less than ¼ of 1% (an order of magnitude less than in the West, and some would say too little to keep the system viable). The Economist estimates cash transactions in India have been reduced by 20% across the country.

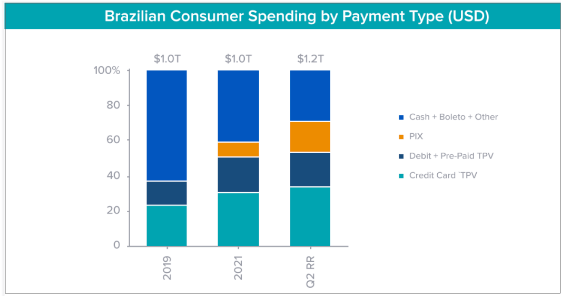

In Brazil, the PIX system has slightly higher fees but many of the same principles. This diagram, also from the a16z FinTech newsletter, clearly shows the migration from cash to PIX:

The impact of this transition is far-reaching: In the future, governments will have new-found tools to distribute funds directly to beneficiaries, particularly in the case of natural disasters, that bypass the old layers of government distribution mechanisms involving traditional banks and payment centers for the non-banked, all which have been vulnerable to graft and corruption along the way.

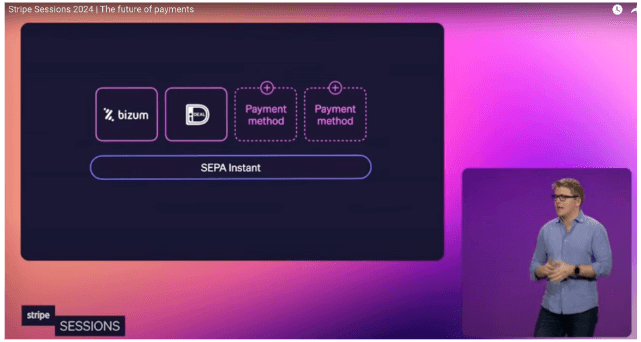

Similar RTP networks have emerged in other parts of the globe, including Europe and the U.S., but in different forms. One of the most notable public versions is the pan-European SEPA Instant Credit Transfer Network (SEPA Instant) managed by the European Payments Council, which was launched in 2017 and is quickly building usage in the Netherlands and Spain. Below is a slide from a Stripe conference showing how new payment brands can plug in or bolt onto underlying RTP “rails”:

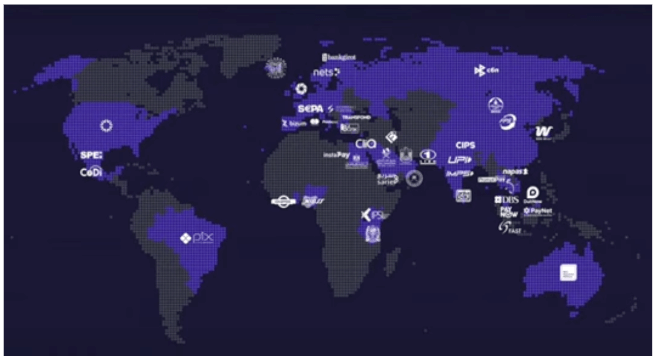

SEPA Instant is still much smaller than its counterparts, only just now approaching one million daily transactions in 2024. Likewise, FedNow is new open RTP network in the U.S. sponsored by the Federal Reserve, but which is still in its infancy. Altogether, there has been a proliferation of new payment systems is taking advantage of these new rails (as shown here from the same Stripe session):

Private Sector Challengers in the West

So far, the fastest growing RTP networks globally have been sponsored by government institutions and tend to have “open” network agenda to be level playing field for participating apps and financial institutions. But private sector alternatives have also been started, primarily in the West, and they are competing with their public sector counterparts.

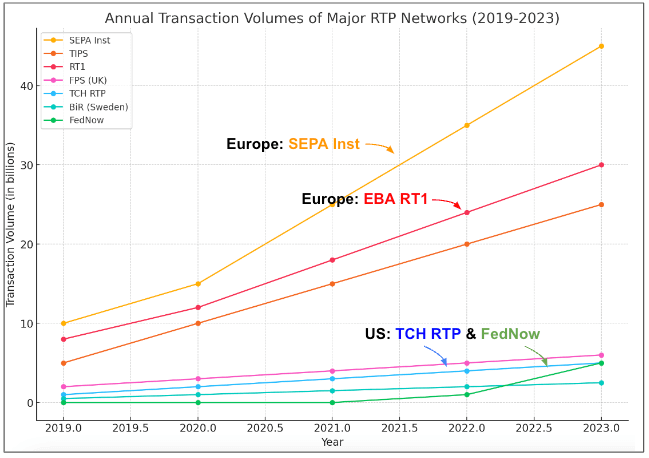

Two examples of fast growing private-sector RTP payment brands are Swish in Sweden and Zelle in the U.S., which are limited to the small group of financial institutions that are their founding members. In the US, the TCH RTP network competes with FedNow, and it is managed by the private-sector The Clearing House (TCH) which is overseen by its 25 large founding member banks. Likewise in Europe, the private-sector EBA Clearing oversees the RT1 network.

In both cases we see public sector and private sector networks competing head on for traffic. Overall, however, Europe is far ahead of US in RTP adoption.

Global Disruptions on the Horizon

One other interesting aspect of “open” RTPs is how they are spreading in the developing world — and potentially inter-linking — in order to provide alternative ways of settling cross-border payments. In India the Modular Open Source Identity Platform (MOSIP) is a new non-profit entity that licenses the UPI code base (mostly developed by InfoSys) to other countries in Africa and elsewhere. These new federated MOSIP systems are estimated to include 100 million new users. By leveraging a common code base, this technology is potentially becoming a new building block for an emerging banking system that will transact across borders without going through SWIFT (U.S. & West) or CIPS (China).

Another way low-cost cross-border payments may happen is the implementation of ISO 20022, which is a new data transmission standard that allows financial institutions to route transaction data in a common form. Some networks like SEPA, FedNow, PIX, Visa and Mastercard have announced plans to embrace it, while others such as UPI and Alipay have not.

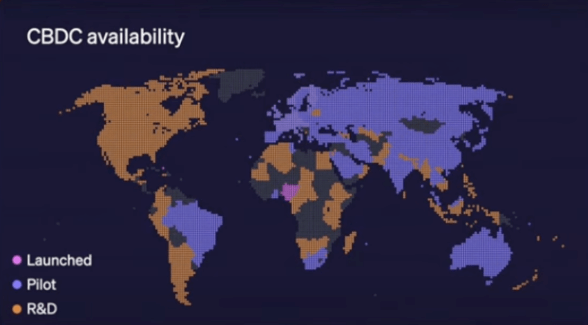

Beyond RTP initiatives, another radical experiment is being driven by Central Banks that are issuing their own special currency, known as a Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC). There are a number of use cases for CBDCs, but one is the ability to bypass intermediary commercial banking layers that add a layer of cost and issue loans directly to businesses at a much lower interest rate. CBDCs are still at the experimentation stage, but interest is spreading globally:

Simple Segmentation of the Current Digital Payments Landscape

To summarize, the following is a quick segmentation and overview of the different types of financial networks that are in use today:

Bank+Card Payment Systems: The dominant system in the West, known primarily by the Visa and Mastercard brands, which are proprietary networks that link financial institutions that agree to participate in that network’s pre-authorization and settlement system. These networks use comparatively fast batch processing to settle payments overnight, and can accept cross-border payments, both of which are significant benefit to merchants. Fees typically include a fixed per-transaction fee plus a small percentage of gross amount. Overall, the downside of these proprietary Bank+Card payment rails is typically higher fees compared to funds from the ACH networks (see below), or straight from a digital wallet. But given the universality of the system, the low settlement risk, and the speed of processing, merchants accept it.

- In the West, Visa and Mastercard are the main networks, with additional networks run by American Express and Discover

- In China, UnionPay is a relatively new system that uses a similar Bank+Card architecture, and that also focuses on cross-border payments that has now grown to 183 countries.

Domestic ACH Networks: These are payment networks for processing ACH transactions, and they operate at lower cost but generally take longer to settle than their proprietary counterparts, usually within a few days as opposed to overnight. Their low fees make them the primary alternative payment rails for small or reoccurring payments which are not as time sensitive, such as consumer bill pay or direct deposit for payroll.

- In the U.S., there are two primary ACH networks that account for roughly 50% of the traffic each: 1) the FedACH network which is initiated by the US Treasury and overseen by the Nacha governing association; and 2) The Clearing House (TCH) Electronic Payments Network called TCH EPN, which is managed by the TCH’s consortium of 25 large member banks. Together they handle the bulk of ACH transactions, and banks can elect which network they use.

- In Europe, the European Central Bank oversees the Single Euro Payments Area (SEPA) network, which crosses borders within Euro-denominated countries. And EPA Clearing maintains its private sector counterparts (EURO1 and STEP1).

Digital Wallet Apps: Often focused primarily on peer-to-peer (P2P) payments, these are local digital repositories that can move funds completely separate from the traditional banking networks. In a POS situation, merchants can theoretically accept payment direct from an app (i.e. wallet to wallet) and not incur banks charges along the way. However, more generally these apps are linked to bank accounts and are transacted as a pass through to the Bank+Card system.

- Consumer brands such as PayPal (and Venmo), CashApp, WePay and Alipay are all well-known examples. These apps are either closed or semi-closed, meaning you can send money to another registered user of PayPal but not from PayPal to a registered user on CashApp.

- Google Pay is closing its independent app in the U.S. and focusing on Google Wallet, but leaving the separate app going in other countries.

Wire Transfer Networks: Whereas debit networks are used primarily domestically for small transactions, other types of networks handle larger B2B transactions, particularly across borders.

- In the U.S., The Clearing House (TCH) operates the CHIPS network for business users, while the Federal Reserve offers the Fedwire system for banks. Internationally, the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT), an international association headquartered in Belgium, maintains an inter-bank network dominated by banks in the West (and which recently took the decision to remove Russian in the wake of the Ukraine conflict).

- Globally, CIPS is an alternative cross-border network being developed by China, and SPFS is a new alternative being pushed by Russia.

Public Sector Fast Payment Networks: Real-Time Payment networks are a new category that, in essence, are like a hybrid between domestic debit networks and the ecosystem of digital payment apps. They have been sponsored primarily by government bodies and are designed from the ground up to settle in real time between banks (or between wallets), but are accessed through third-party apps, all of which can intercommunicate because they are using a common rails and identity system. The governing body regulates transaction fees.

- Globally, UPI in India and PIX in Brazil are the two best known examples. However, new instances of these networks are spreading globally, including through the work of technology providers like MOSIP, which is spearheading distribution of the technology to developing economies.

- In the U.S., FedNow is a new initiative in the U.S. by the Federal Reserve Bank that has similar characteristics to an open RTP by trying to include as many small banks as possible, but so far adoption has been slow.

- In Europe, SEPA Instant is a European version of an RTP and managed by the same SEPA consortium that manages the debit network and licenses different consumer brands to interface with it.

Private Sector Fast Payment Networks: Other types of RTP networks have been developed by consortiums of private banks that offer the same fast settlement process, but which are generally not open to 3rd party brands beyond the consortium. In Sweden, Swish is a fast payments network launched in 2012 by a consortium of 6 banks, and has since generated a near monopoly on digital payments in the country.

- In the U.S., there are multiple examples. Zelle is a fast payment network started by a small consortium of banks called Early Warning Services LLC, but rather than support independent apps, it instead functions within each member’s banking app.

- Meanwhile TCH (The Clearing House), which manages one of the main ACH networks and is governed by a broader consortium of 25 banks, has launched TCH RTP and continues to grow modestly quarter on quarter (2-5%).

- In Europe, the largest private sector RTP network is EBA RT1, which competes with SEPA Inst.

Crypto Networks (Bitcoin, Ether, etc.): These are networks that issue their own digital currencies and settle across distributed nodes, which are synchronized to have multiple records of all transactions, usually referred to as blockchains. Bitcoin and Ether are well-known examples, but their usage as alternatives to other digital payments networks for day-to-day use has been minimal because of the multi-note settle architecture.

Check out some of my other coverage on this topic: