For over a decade we’ve been sounding the alarm on Intel. Five years ago, like some on Wall Street, we recommended a strategy to recreate Intel by splitting up its design and manufacturing divisions. Most recently we posited that a miracle would be needed for Intel to achieve its aspirations of becoming a viable number two foundry by 2030. The majority of industry pundits have finally come to the realization that Intel’s current path is unsustainable. However some still feel that splitting Intel’s fabs from its design business doesn’t make sense.

We disagree.

In this post, we reiterate that Intel in our view has no choice but to shed its vertically integrated heritage and transform the company into a leading designer of chips for emerging multi-trillion dollar markets. In our opinion, Intel’s design business would thrive if it could shed the weight of Foundry.

We recognize that Intel’s foundry business has negative paper value. The company’s predicament is reminiscent of IBM’s Microelectronics division, when it actually paid Global Foundries $1.5B to take its manufacturing operation off its hands (and committed $3B to ongoing semiconductor research). Intel should be so lucky, perhaps forming a manufacturing alliance with another foundry. Exploring that scenario is not the purpose of this post, but we acknowledge the “how” in this equation is important.

TL;DR

When PC volumes peaked in 2012, Intel’s manufacturing cost advantages began to wane. Arm wafer volumes exploded with the adoption of smartphones. These volumes surpassed those of x86 and conferred major cost and time-to-market advantages to TSMC and its design partners like Apple, AMD, NVIDIA and Qualcomm.

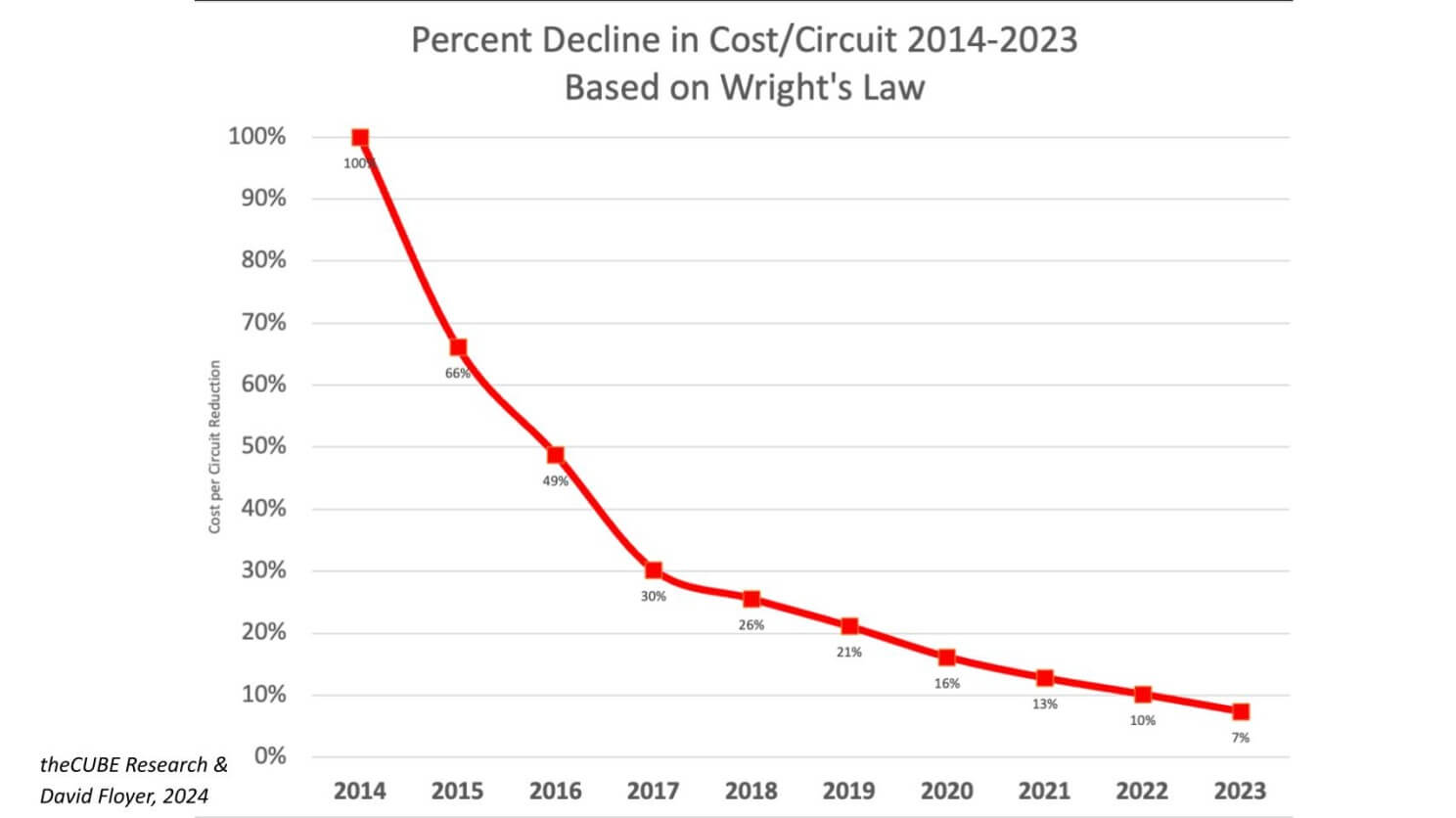

The impact of volume manufacturing on costs can be explained by Wright’s Law. For decades, Wright’s Law has been a guiding principle in manufacturing generally and the semiconductor industry specifically. It explains how production efficiencies and cost reductions follow learning curves. The law remains central to understanding technological advancement and cost reduction over time and is particularly applicable to the chip business.

Wright’s Law was the driving force behind x86’s ascendency and the demise of RISC. It was the culprit that caused Global Foundries to back out of its committed agreement with IBM to supply advanced processes for future generations of IBM designs. And Wright’s Law explains why Intel will be unable to cost effectively compete for advanced chips.

In a word…volume.

The volume disadvantage Intel faces relative to TSMC creates creates a dynamic where it can’t compete on cost without virtually unlimited access to capital. We believe this disadvantage is insurmountable in a reasonable timeframe and as such leaves Intel only one viable option, to finally capitulate to market forces and shed its manufacturing division.

The Immutability of Wright’s Law

Wright’s Law posits that costs decline predictably as cumulative production volumes increase. Historically, this relationship has proven immutable, with market dynamics and supply constraints causing only short-term deviations. Analysts and engineers alike often discuss how far into the future this trend can continue. Currently, there is hope that Wright’s Law will remain effective up to the production of 1.5nm and 1nm chips, with vertical chip scaling and new technologies offering cost benefits that outweigh their development expenses.

Looking beyond these technological thresholds, the belief persists that engineers will continue to make advancements that drive down the cost per circuit, reinforcing Wright’s Law for at least another decade. The law’s long-term immutability hinges on engineering innovations continuing at the same pace. Historically, each prediction that the law would fail has been followed by breakthroughs that extended its lifespan.

Chart 1: Annual Cost/Circuit Declines Relative to 2014 Costs

The Case of Intel: Once Dominant, Now Vulnerable

For Intel, Wright’s Law once represented a formidable moat. Because Intel had the highest wafer volumes, thanks to its market share in PCs, it was able to protect profitability by capitalizing on its leadership in semiconductor manufacturing. Importantly, it was always first to market with the most advanced chips and it maintained a cost advantage for decades. In the 1990’s Intel dominated the semiconductor market. Its volume lead in PCs allowed the company to move up market with its x86 architecture and surpass high end competitors like HP, IBM, and Sun, capturing 95% of the server market. However, as semiconductor manufacturing moved towards smaller nodes, Intel’s once dominant position began to erode.

By 2012, two significant shifts occurred that undermined Intel’s advantage: 1) Arm chip designs, which were manufactured by TSMC and Samsung, entered the market, providing consumer devices with higher wafer volumes and lower costs than Intel’s offerings; and 2) Intel’s ability to leverage Wright’s Law began to falter as PC volumes peaked and it lost the manufacturing edge it once had.

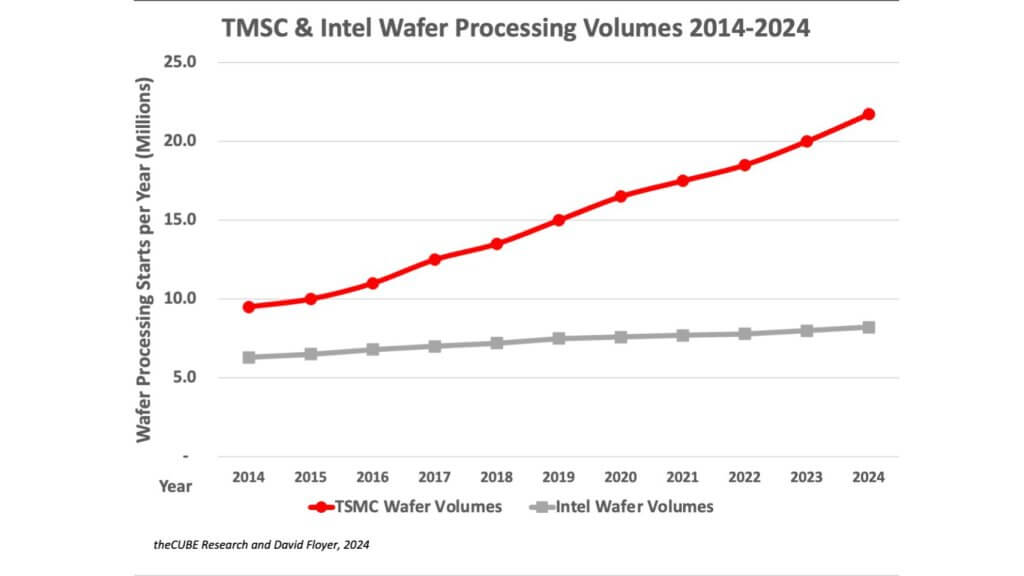

Chart 2: Intel and TSMC Wafer Volumes, 2014 – 2024

The above chart describes the volume dynamic between Intel and TSMC subsequent to PC volumes peaking. The fundamentals that conferred competitive advantage to Intel for decades suddenly flipped to the benefit of TSMC. This was directly related to the introduction and ascendency of the iPhone and other modern smartphones, a market Intel initially chose to ignore.

Wright’s Law in a Declining Market

When a company leads in production volume, Wright’s Law is a powerful force for sustaining competitive advantage. However, as Intel’s market share diminished, the law turned against it. In a declining market, Wright’s Law becomes “savage,” as the cost advantages it once provided now favor competitors with higher production volumes.

Intel’s foundry business, which once reigned supreme, is now facing overwhelming pressure. Development costs rise as a percentage of revenue, making it difficult to remain competitive against TSMC, which continues to produce chips at lower costs and higher volumes. Moreover, potential customers of Intel’s foundry services expect lower prices and delivery guarantees, putting further strain on Intel’s financials.

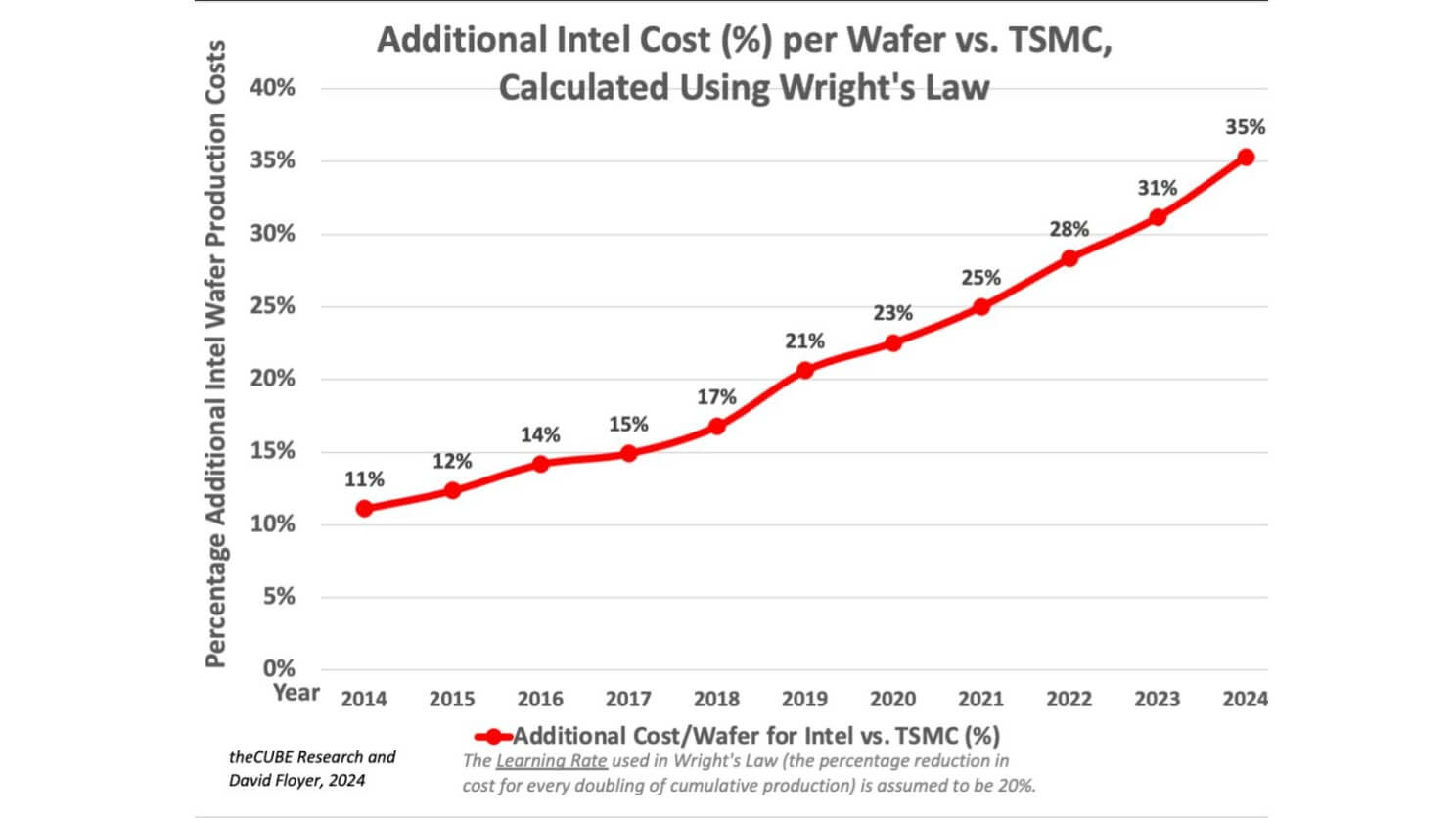

The chart below depicts the relative cost per wafer for Intel vs. TSMC using Wright’s Law. It shows that over time, Intel falls further behind TSMC directly because of learning curve dynamics. In the early years of this chart, Intel could hide a 10-15% cost disadvantage. At today’s 35% delta, Intel simply can’t compete without unlimited capital.

Chart 3: Intel’s Cost of Wafer Production Continues to Increase Relative to TSMC

We recognize that Intel’s aspirations are to surpass Samsung, not TSMC. But practically speaking Samsung faces many similar challenges to Intel. Perhaps not as acute because Samsung has more volume from its Android business and other lines of business that throw off substantial cash. Nonetheless, the market price for advanced chips is set by TSMC and that is the benchmark any manufacturer must target to win share.

Intel now faces a critical decision. If it continues to compete head-to-head with TSMC in manufacturing, it risks financial instability, even bankruptcy. A more probable path in our view is divesting its foundry division to focus the company on chip design and device production. This would allow Intel to concentrate on creating innovative x86, Arm and RISC-V designs while outsourcing manufacturing to the likes of TSMC, thereby reducing risk and capital expenditure.

To summarize, the impact of Wright’s Law and its implied learning curve effects on Intel’s business is twofold:

- Because its volume is lower, Intel’s cost per wafer is increasingly non-competitive, making it virtually impossible to gain enough share to effectively compete.

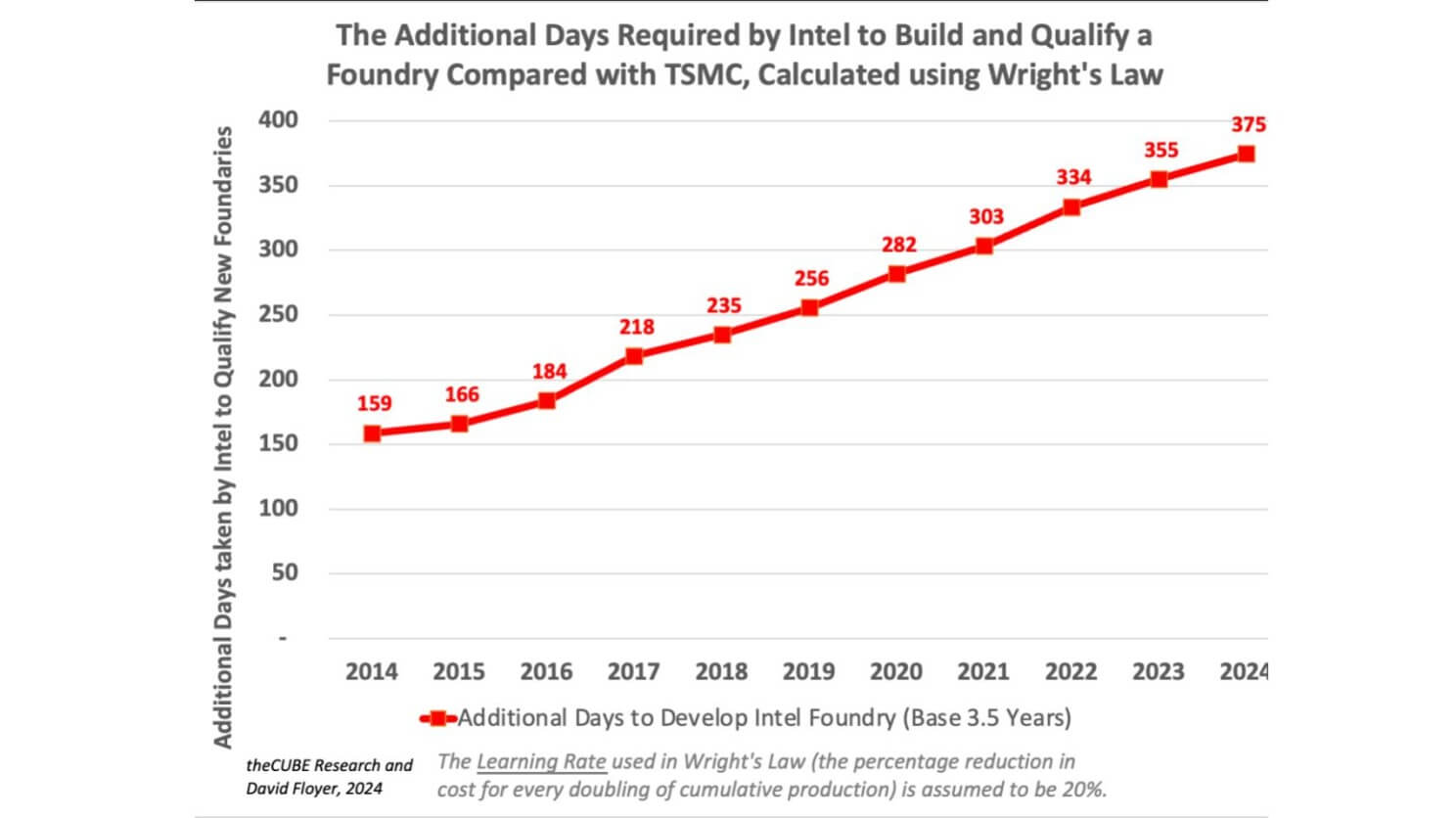

- It takes Intel much longer than TSMC to achieve productive foundry output and qualify new wafer processes (see chart below).

Chart 4: Intel’s Time to Market Disadvantage on New Foundries

In theory, Gelsinger’s integrated strategy is correct, if he had access to virtually infinite capital. But in our estimation, it would take hundreds of billions of dollars to approach TSMC’s volume. In this scenario, Intel would have to tank market pricing and take massive incremental losses for years in order to win the business and increase volumes to get on the right side of the Wright’s Law learning curve. Similar dynamics apply to catching Samsung because TSMC sets the market.

Strategic Scenarios for Intel

Intel, by our estimates, if it continues on its current path, has possibly two years before it loses access to sources of capital. This means the clock is currently striking twelve and Cinderella’s coach is about to turn into a pumpkin. There are three scenarios that could preserve Gelsinger’s vision:

- China invades Taiwan and takes control of TSMC within a year. The US, other western governments, and perhaps big tech, move in to preserve Intel’s viability as a manufacturer. We acknowledge this scenario is plausible, but in our view, China’s leadership will likely wait until Intel makes its next move and massive US debts make the scenario difficult to envision.

- The US military subsidizes Intel. This will buy Intel more time but the end game is inevitable in our view.

- Intel divests its foundry business.

In the short term, Intel’s design teams must continue to rely on TSMC to remain competitive with AMD in the x86 market. This dependence on an external manufacturer underscores the limitations of Intel’s foundry capabilities. Over the long term, however, Intel has an opportunity to reorient its strategy around Arm and RISC-V technologies, which offer a path to reducing design costs while maintaining access to TSMC’s cutting-edge manufacturing.

Further, we believe that Intel should rethink its design business and potentially vertically integrate up the stack and capture more of the value in PCs, servers and edge devices. While one can argue that Intel is already doing so in x86, our thinking is Intel should continue to ride its x86 monopoly but extend innovation with Arm and RISC-V designs.

By divorcing its design division from its foundry business, Intel could allow the design side of the company to thrive without being weighed down by the capital-intensive and unprofitable manufacturing division. Such a move would not only mitigate financial risk but also allow Intel to focus on what it does best: innovating in chip design.

Conclusion: The Future of Wright’s Law and Intel

The question remains: Will Wright’s Law continue to hold true, especially in light of Intel’s struggles and the shifting dynamics of the semiconductor market? In our view, Wright’s Law will continue to govern the semiconductor industry, at least for the foreseeable future. Technological advancements in chip design and manufacturing will allow it to hold true through the 1.5nm and 1nm processes. However, Intel’s struggles serve as a stark reminder that no company is immune to the economic forces that Wright’s Law represents. Once a leader, Intel must now adapt to survive.

The most likely outcome is that Intel will divest its foundry operations and refocus on chip design, allowing it to remain competitive in an industry where Wright’s Law still reigns supreme. The immutable nature of Wright’s Law means that those who fall behind in production volume will struggle to catch up, as Intel has learned the hard way. Ultimately, engineering innovations will continue to drive the industry forward, but only those companies that adapt to the realities of Wright’s Law will thrive.

Watch the excerpt on this topic from this week’s CUBE Pod: